/TEACHING

GD 303: Experimental Design Practices

Spring 2023

Speculative Design Student Project

Project New Dawn

Spring 2023

Speculative Design Student Project

Project New Dawn

Note: I’ve chosen to anonymize this student because of the sensitive nature of this project.

This student’s Speculative Design project is one of the most disturbing and plausible narratives about the future of the US Military that I’ve ever seen.

As I say to my students each year in the Speculative Design (SD) assignment, as well as throughout my writing about Speculative Design in general, SD can be—and often is—deeply flawed and problematic. Its history is rife with eurocentrism and an erasure of folks in the “global south” who are suffering the fates on which designers in the “global north” are speculating. However, I do believe that SD as an intellectual exercise, especially at the late undergraduate level, has some redeeming qualities that make it worth teaching. I think that this student’s project is a good example of why.

This student began with a simple question on which they were interested in speculating (in part because of their own experience in the military): “what would happen if the US Military is unable to recruit people based on the volunteer system?” But, after I screened the brilliant film, Sleep Dealer, this student combined this question with another question that feels pressing to many—what will happen with the increasing number of migrants to the US, crossing, primarily, but not always, at the southern border? The intersection of these two questions became the core of this student’s Speculative Design project, which they titled “Project New Dawn.”

Inspired by projects like Superflux’s Dynamic Genetics vs. Mann, Walid Ra’ad’s Atlas Group, and the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, the student created a fictional archive of leaked government documents that tell the story of a covert project intended to incentivize immigrants to enlist in the US military while shielding the government from responsibility for the deaths of these not-yet citizen “volunteers.”

The project website—from which viewers enter this archive—states:

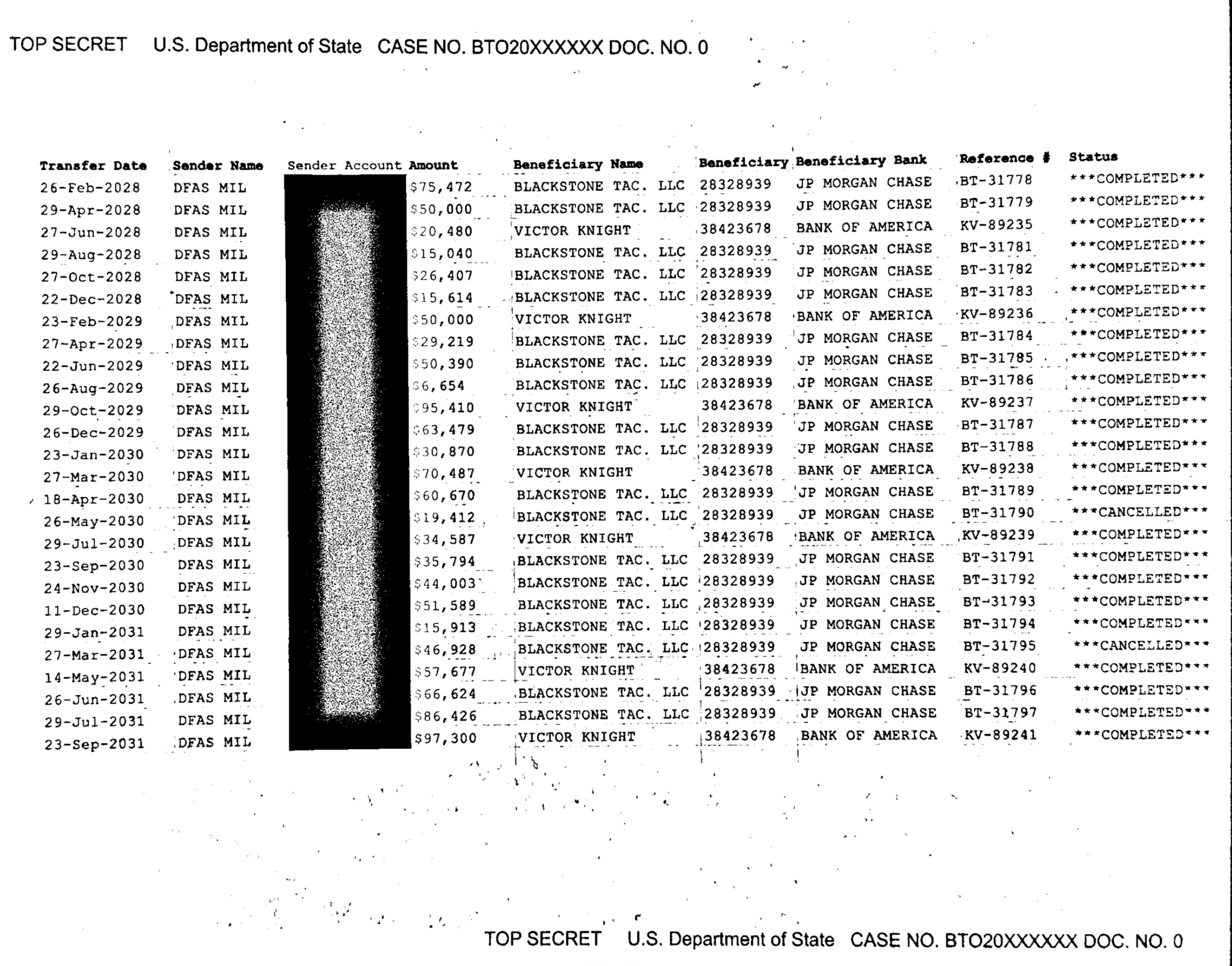

“2028: The U.S. government covertly launched the AMERICAN HERO PROGRAM (AHP), allegedly offering undocumented non-U.S. citizens a gateway to permanent residency through military enlistment. designed to address the escalating immigration crisis and the military’s chronic recruitment shortfalls. This controversial scheme has drawn widespread criticism and suspicion... On February 2, 2032, a bombshell revelation hit the public domain: documents were leaked unveiling a series of wire transfers from the U.S. Department of Defense to the shadowy private military firm, BLACKSTONE TACTICAL OPERATIONS. These transactions, totaling a staggering 1.2 million dollars over three years, hint at a deeper, more sinister agenda.”

The attention to detail in this fictional archive is astonishing. The student carefully studied the formatting and naming conventions of military documents, then produced, printed, altered, and scanned the fictional documents in order to create a disorienting sense of realism. Without the cue to viewers that this archive is, indeed, from the future, it would be nearly impossible to tell that this isn’t happening in the present. I’m not sure for how long the Project New Dawn website will remain live, but if you are able to visit this archive, please do.

Mimicking in many ways the history of the Bracero program, which served as another point of departure for this project, the Project New Dawn archive traces the journey of one Diego Morales, who, after being caught crossing the US-Mexico border illegally, enlists through the AHP to avoid the consequences of his migration. Diego ends up working for Blackstone and is killed in combat, but the record of his existence, much less his military service, is erased. Diego, the archive suggests, is part of a growing migrant military labor force that, like other forms of migrant labor, enables employers to circumnavigate employment rules and regulations.

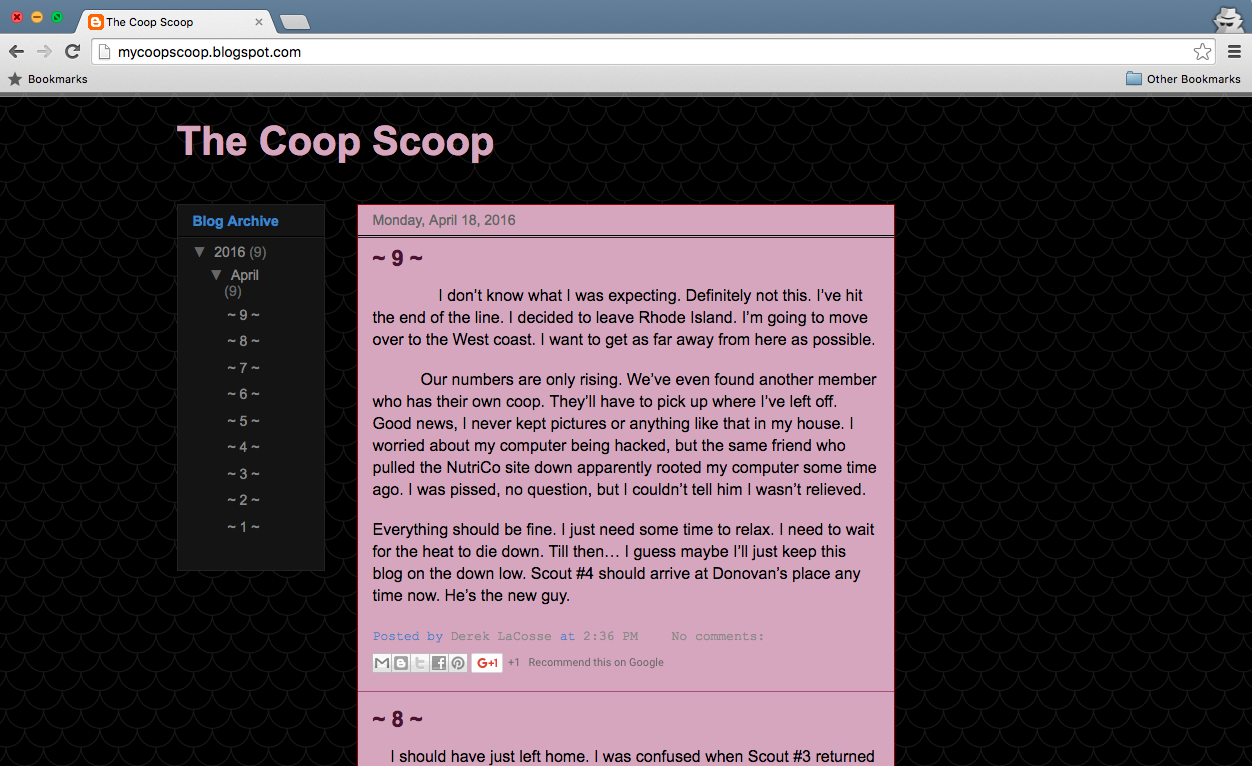

Below: a screenshot of the interface to the archive.

This student’s Speculative Design project is one of the most disturbing and plausible narratives about the future of the US Military that I’ve ever seen.

As I say to my students each year in the Speculative Design (SD) assignment, as well as throughout my writing about Speculative Design in general, SD can be—and often is—deeply flawed and problematic. Its history is rife with eurocentrism and an erasure of folks in the “global south” who are suffering the fates on which designers in the “global north” are speculating. However, I do believe that SD as an intellectual exercise, especially at the late undergraduate level, has some redeeming qualities that make it worth teaching. I think that this student’s project is a good example of why.

This student began with a simple question on which they were interested in speculating (in part because of their own experience in the military): “what would happen if the US Military is unable to recruit people based on the volunteer system?” But, after I screened the brilliant film, Sleep Dealer, this student combined this question with another question that feels pressing to many—what will happen with the increasing number of migrants to the US, crossing, primarily, but not always, at the southern border? The intersection of these two questions became the core of this student’s Speculative Design project, which they titled “Project New Dawn.”

Inspired by projects like Superflux’s Dynamic Genetics vs. Mann, Walid Ra’ad’s Atlas Group, and the Guantanamo Bay Museum of Art and History, the student created a fictional archive of leaked government documents that tell the story of a covert project intended to incentivize immigrants to enlist in the US military while shielding the government from responsibility for the deaths of these not-yet citizen “volunteers.”

The project website—from which viewers enter this archive—states:

“2028: The U.S. government covertly launched the AMERICAN HERO PROGRAM (AHP), allegedly offering undocumented non-U.S. citizens a gateway to permanent residency through military enlistment. designed to address the escalating immigration crisis and the military’s chronic recruitment shortfalls. This controversial scheme has drawn widespread criticism and suspicion... On February 2, 2032, a bombshell revelation hit the public domain: documents were leaked unveiling a series of wire transfers from the U.S. Department of Defense to the shadowy private military firm, BLACKSTONE TACTICAL OPERATIONS. These transactions, totaling a staggering 1.2 million dollars over three years, hint at a deeper, more sinister agenda.”

The attention to detail in this fictional archive is astonishing. The student carefully studied the formatting and naming conventions of military documents, then produced, printed, altered, and scanned the fictional documents in order to create a disorienting sense of realism. Without the cue to viewers that this archive is, indeed, from the future, it would be nearly impossible to tell that this isn’t happening in the present. I’m not sure for how long the Project New Dawn website will remain live, but if you are able to visit this archive, please do.

Mimicking in many ways the history of the Bracero program, which served as another point of departure for this project, the Project New Dawn archive traces the journey of one Diego Morales, who, after being caught crossing the US-Mexico border illegally, enlists through the AHP to avoid the consequences of his migration. Diego ends up working for Blackstone and is killed in combat, but the record of his existence, much less his military service, is erased. Diego, the archive suggests, is part of a growing migrant military labor force that, like other forms of migrant labor, enables employers to circumnavigate employment rules and regulations.

Below: a screenshot of the interface to the archive.

Below: ads for the American Hero Program (AHP)

/TEACHING

Experimental Design Practices Course (GD 303)

Michigan State University

2017-2019

At the outset of my appointment at MSU in 2014, I began working to reshape parts of the Graphic Design program to align with contemporary and emergent practices in the design disciplines, which are undergoing an immense amount of change. Part of this effort included the redesign of a course formerly known as “Design Thinking.”

The new course, “Experimental Design Practices” (EDP), which first ran in 2017, sought to introduce students to different ways of thinking about design and what it offers to society. It is also about the future of “design” and what it’s edges and contours might look like. What kind of course is a design course for the 21st century and beyond? And who should be able to participate in it? This course is an attempt at answering those questions through both its curricular structure and its openness to all majors.

EDP intended to introduce students to a number of aspects of design, and in this sense, it was somewhat of a hybrid “studio-survey” course. EDP aimed to introduce students to practices of design that might operate at the margins of the constellation of design disciplines, but might have something important to teach us when it comes to creating just and equitable futures.

Acknowledging the inherent limitations of the course, it covered (briefly, as mentioned above) three different modes/frameworks of design.

Michigan State University

2017-2019

At the outset of my appointment at MSU in 2014, I began working to reshape parts of the Graphic Design program to align with contemporary and emergent practices in the design disciplines, which are undergoing an immense amount of change. Part of this effort included the redesign of a course formerly known as “Design Thinking.”

The new course, “Experimental Design Practices” (EDP), which first ran in 2017, sought to introduce students to different ways of thinking about design and what it offers to society. It is also about the future of “design” and what it’s edges and contours might look like. What kind of course is a design course for the 21st century and beyond? And who should be able to participate in it? This course is an attempt at answering those questions through both its curricular structure and its openness to all majors.

EDP intended to introduce students to a number of aspects of design, and in this sense, it was somewhat of a hybrid “studio-survey” course. EDP aimed to introduce students to practices of design that might operate at the margins of the constellation of design disciplines, but might have something important to teach us when it comes to creating just and equitable futures.

Acknowledging the inherent limitations of the course, it covered (briefly, as mentioned above) three different modes/frameworks of design.

-

Inclusive, Universal, and Accessible Product/Service Design

-

Interrogative Design

- Speculative and Critical Design

Above: Moriah Bender (BA ’18) created an intervention to raise awareness about refugees. Her project utilized the life vest as both an attractive surface as well as a symbolic object to draw viewers into conversation with her work.

Unit 1: Inclusive, Universal, and Accessible Product/Service Design

The question is not “are you disabled” but “when will you be disabled.”

– Elizabeth Guffey, Bess Williamson, Helen Armstrong, Farnaz Nickpour, 2018

The first unit, on Inclusive, Universal, and Accessible Design is probably the most familiar to students. It’s not so radically different from their understanding of what “design” is. This unit asks students to consider how “everyday life” is experienced by people who fall outside of the “norm” for which most design is created. In this project, students choose an everyday object or system and redesign it to make it more inclusive and/or accessible. What they choose to redesign and how they do so is up to them. In the end, this is an exercise in trying to think about others who are not just “users” but people, people who are different than each one of us, who have differing embodied experiences of everyday life.

To this end, the readings for this unit include Ben Highmore’s introduction to the theory of “everyday life” in the Everyday Life Reader and Lennard Davis’ “Normality, Power, and Culture,” the introduction to the Disability Studies Reader. Students also study the work of Sara Hendren and learn about the history of Universal Design and its genesis at NC State.

Students produce prototypical interventions that demonstrate their learning. Part of the project is acknowledging that the objects the students produce themselves might fail, or that they might only be a rough prototype. A polished design product is not the goal. An appreciation of a process that foregrounds inclusivity is of the highest importance.

The question is not “are you disabled” but “when will you be disabled.”

– Elizabeth Guffey, Bess Williamson, Helen Armstrong, Farnaz Nickpour, 2018

The first unit, on Inclusive, Universal, and Accessible Design is probably the most familiar to students. It’s not so radically different from their understanding of what “design” is. This unit asks students to consider how “everyday life” is experienced by people who fall outside of the “norm” for which most design is created. In this project, students choose an everyday object or system and redesign it to make it more inclusive and/or accessible. What they choose to redesign and how they do so is up to them. In the end, this is an exercise in trying to think about others who are not just “users” but people, people who are different than each one of us, who have differing embodied experiences of everyday life.

To this end, the readings for this unit include Ben Highmore’s introduction to the theory of “everyday life” in the Everyday Life Reader and Lennard Davis’ “Normality, Power, and Culture,” the introduction to the Disability Studies Reader. Students also study the work of Sara Hendren and learn about the history of Universal Design and its genesis at NC State.

Students produce prototypical interventions that demonstrate their learning. Part of the project is acknowledging that the objects the students produce themselves might fail, or that they might only be a rough prototype. A polished design product is not the goal. An appreciation of a process that foregrounds inclusivity is of the highest importance.

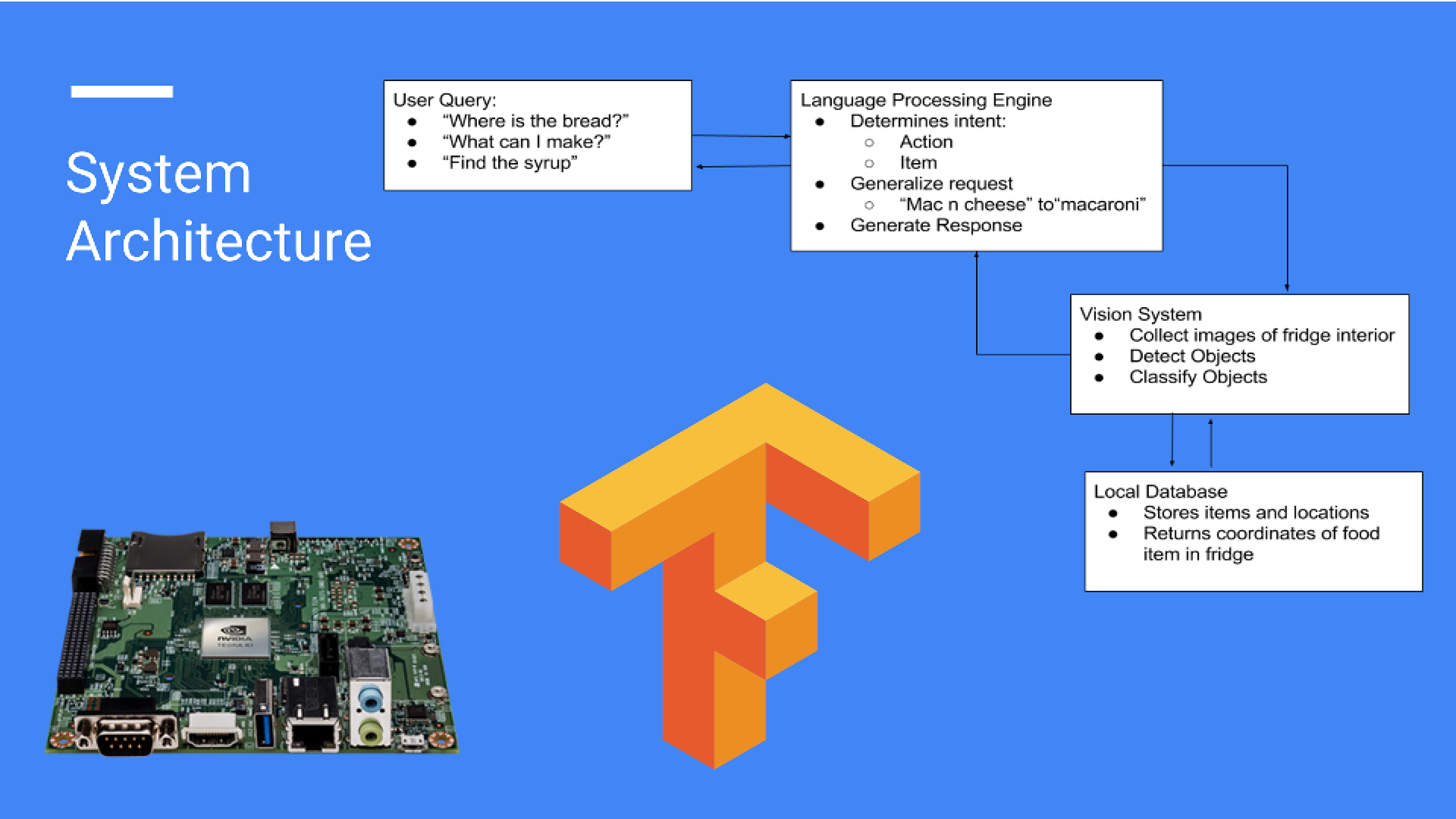

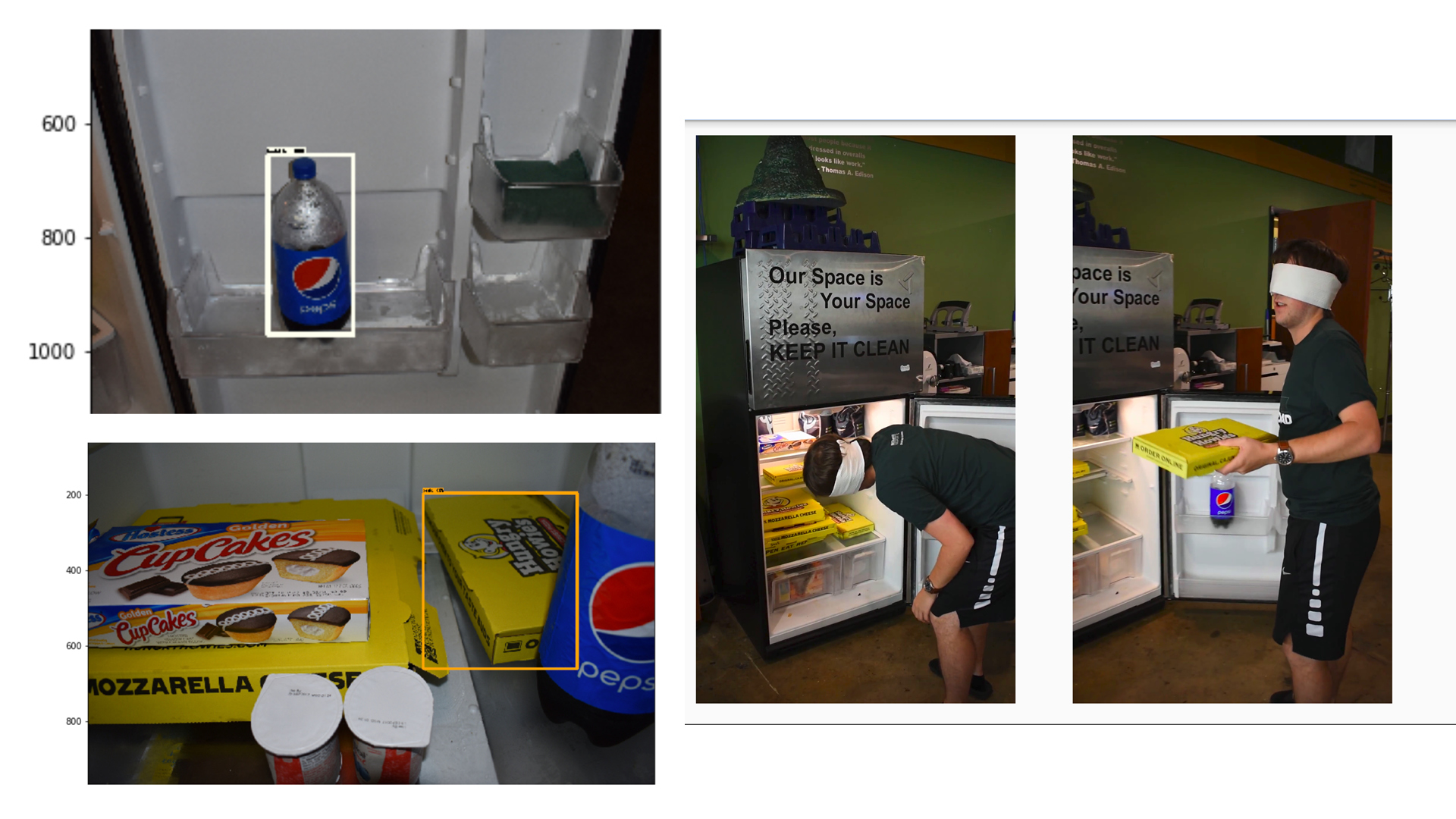

Above: Scott Swarthout (BS, Computer Science, 2018) created a concept for a combination computer-vision/voice-interaction system that would allow blind users to navigate their refrigerators through a conversational interface.

Below: Jacob Chaban (BFA, Graphic Design, 2020) worked with his grandfather to prototype an object that could help elderly users navigate stairways and hold onto railings with more ease, while accommodating different railing types.

Below: Jacob Chaban (BFA, Graphic Design, 2020) worked with his grandfather to prototype an object that could help elderly users navigate stairways and hold onto railings with more ease, while accommodating different railing types.

Unit 2: Interrogative Design

The second unit of the course is based on the work of Krzysztof Wodiczko, who termed his artistic/design practice “Interrogative Design.”

In the introduction to his monograph, Critical Vehicles, Wodiczko writes: “I attempt to detect and trace conditions of life under the illusion or delusion of freedom—the hypocritical life we lead when we take refuge in the machine of a political or cultural system while closing one eye to the implications of our own passivity or, frankly speaking, complicity… The danger lies in allowing oneself to live in something Andrzej Turowski called ideosis—the commonsense life of well-calculated choices for navigating through the system by claiming a critical or independent perspective on it. If democracy is to be a machine of hope, it must retain one strange characteristic—its wheels and cogs will need to be lubricated not with oil but with sand… My work attempts to heal the numbness that threatens the health of the democratic process by pinching and disrupting it, waking it up, and inserting the voice, experiences, and presence of those others who have been silenced, alienated, and marginalized.”

Wodiczko goes on: “In short, the critical vehicle is an “ambitious” and “responsible” medium—a person or piece of equipment—that attempts to convey ideas and emotions in the hope of transporting to each human terrain a vital judgment toward a vital change.” He suggests that his practice of “Interrogative Design” brings “critical methods and new, perhaps difficult to accept but vital, functional programs to the design of tactical equipment.” (emphasis mine)

This second project, then, asks students to produce a piece of “equipment,” a vehicle for communication, that will make visible the invisible, that will render in a new way something or someone that is marginalized or hidden because of the sociopolitical-economic structure of everyday life.

Again, the project is not intended to produce polished design outcomes but rather prototypical objects and documentation that help students appreciate a different orientation towards the role of design and its potential within society—one that does not serve to solve problems in a narrowly construed, capitalist-instrumentalist sense, but rather one that seeks to reveal that which is marginalized, invisible, or intentionally concealed.

The second unit of the course is based on the work of Krzysztof Wodiczko, who termed his artistic/design practice “Interrogative Design.”

In the introduction to his monograph, Critical Vehicles, Wodiczko writes: “I attempt to detect and trace conditions of life under the illusion or delusion of freedom—the hypocritical life we lead when we take refuge in the machine of a political or cultural system while closing one eye to the implications of our own passivity or, frankly speaking, complicity… The danger lies in allowing oneself to live in something Andrzej Turowski called ideosis—the commonsense life of well-calculated choices for navigating through the system by claiming a critical or independent perspective on it. If democracy is to be a machine of hope, it must retain one strange characteristic—its wheels and cogs will need to be lubricated not with oil but with sand… My work attempts to heal the numbness that threatens the health of the democratic process by pinching and disrupting it, waking it up, and inserting the voice, experiences, and presence of those others who have been silenced, alienated, and marginalized.”

Wodiczko goes on: “In short, the critical vehicle is an “ambitious” and “responsible” medium—a person or piece of equipment—that attempts to convey ideas and emotions in the hope of transporting to each human terrain a vital judgment toward a vital change.” He suggests that his practice of “Interrogative Design” brings “critical methods and new, perhaps difficult to accept but vital, functional programs to the design of tactical equipment.” (emphasis mine)

This second project, then, asks students to produce a piece of “equipment,” a vehicle for communication, that will make visible the invisible, that will render in a new way something or someone that is marginalized or hidden because of the sociopolitical-economic structure of everyday life.

Again, the project is not intended to produce polished design outcomes but rather prototypical objects and documentation that help students appreciate a different orientation towards the role of design and its potential within society—one that does not serve to solve problems in a narrowly construed, capitalist-instrumentalist sense, but rather one that seeks to reveal that which is marginalized, invisible, or intentionally concealed.

Above: Jacob Chaban created a mobile museum of workplace injuries, which is accompanied by a brochure on the increasing rate of injuries in workplaces dominated by metrics, such as Amazon’s warehouses.

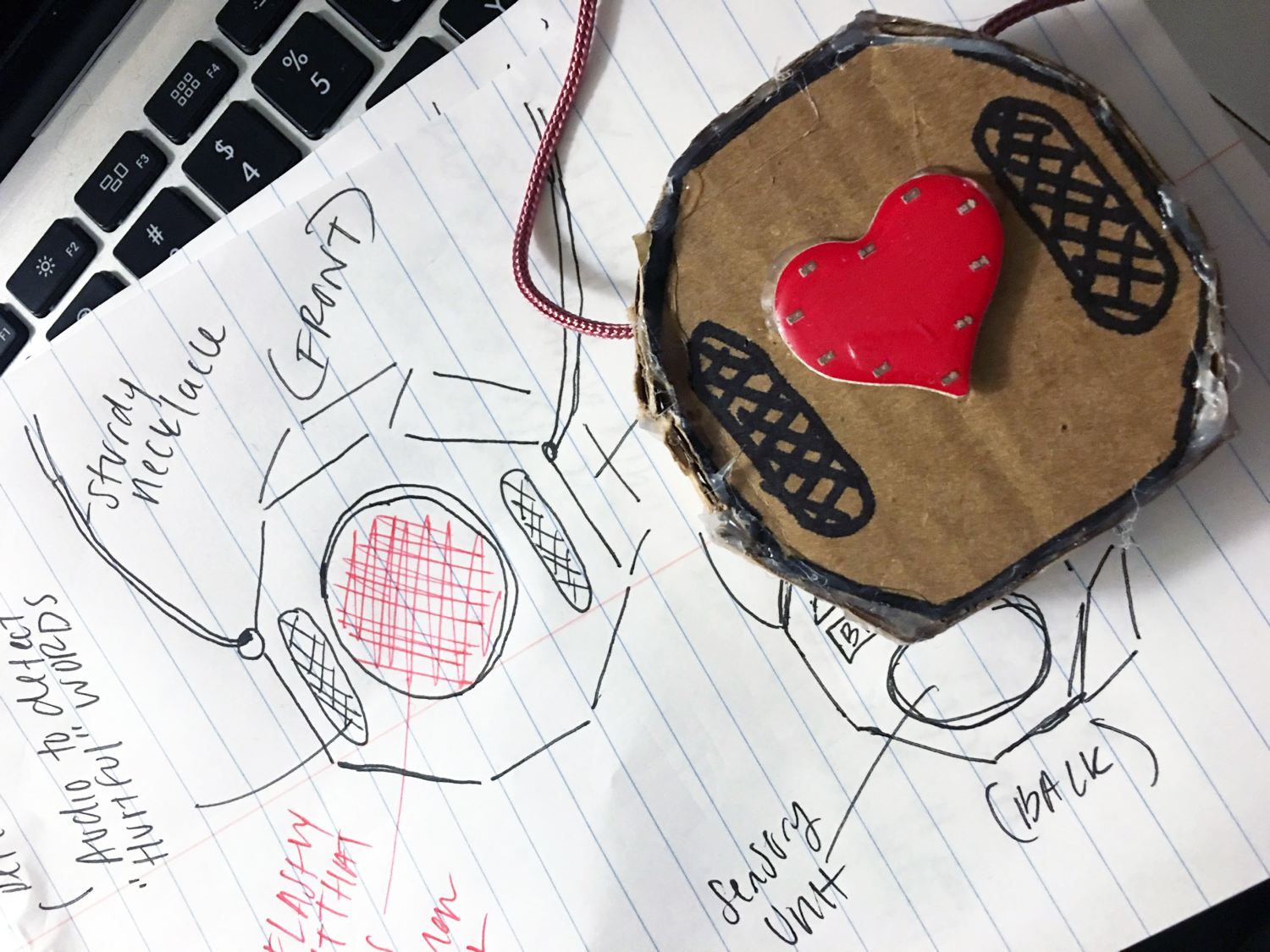

Above: Liz Vangyi’s project was beautiful and brilliant. She created a pendent intended to allow its wearer to communicate when they are experiencing a microaggression. It combines biometric feedback from the wearer with manual activation, lighting up when its wearer feels as though they are experiencing a microaggression by the person with whom they are speaking. This object then functions as a kind of mediator, its artifice drawing the aggressor into conversation with the wearer in a new way, giving the wearer an opportunity to explain what they are experiencing.

Above: Tessa Wegman (BFA ‘19) created a series of “prayer cards” that are actually about the rampant sexual abuse within the Catholic Church. She took the form of the traditional Catholic prayer card and subverted it, using her design skills to create a seductive aesthetic that draws viewers to the work.

Unit 3: Speculative/Critical Design and the Future of Everyday Life

Speculative Design is one of the more well-known and one of the more problematic branches amongst the newly codified (see UCSD’s Speculative Design undergraduate degree) forms of design practice/research. This final unit asks students to engage with a practice of examining certain sociotechnical trajectories and to speculate on them. At its very best, Speculative Design is a powerful and unique mode of questioning, interrogating, and critiquing the various futures that might emerge from the dynamic interactions of ideologies, social relations, environmental conditions, and technological innovation. Benjamin Bratton writes that “Speculative Design focuses on possibilities and potentials. It confronts an uncertain and ambiguous future and seeks to give it shape.” At its best, SD asks questions about the norms and values of societies in which its speculations would exist. In doing so, it asks us whether we might want to live in those societies, and if those values are ones by which we want to live and be governed in the future.

In this project, students produce prototypical artifacts that emerge from the development of a story about the future. This story reflects research the students do on emerging technologies and the way in which those technologies might be situated within certain political-economic regimes. Students therefore consider the physical and ideological landscape within which the technologies on which they speculate are situated.

Unit 3: Speculative/Critical Design and the Future of Everyday Life

Speculative Design is one of the more well-known and one of the more problematic branches amongst the newly codified (see UCSD’s Speculative Design undergraduate degree) forms of design practice/research. This final unit asks students to engage with a practice of examining certain sociotechnical trajectories and to speculate on them. At its very best, Speculative Design is a powerful and unique mode of questioning, interrogating, and critiquing the various futures that might emerge from the dynamic interactions of ideologies, social relations, environmental conditions, and technological innovation. Benjamin Bratton writes that “Speculative Design focuses on possibilities and potentials. It confronts an uncertain and ambiguous future and seeks to give it shape.” At its best, SD asks questions about the norms and values of societies in which its speculations would exist. In doing so, it asks us whether we might want to live in those societies, and if those values are ones by which we want to live and be governed in the future.

In this project, students produce prototypical artifacts that emerge from the development of a story about the future. This story reflects research the students do on emerging technologies and the way in which those technologies might be situated within certain political-economic regimes. Students therefore consider the physical and ideological landscape within which the technologies on which they speculate are situated.

Above: For the third project on Speculative Design, Josh Hutchison (BFA ‘20) produced artifacts from a provocative and ambiguously dystopian (or utopian?) future in which Amazon has partnered with governments around the world to create privatized communities that house displaced persons, outcasts, refugees, and otherwise abandoned people (hence the name for the project, DOLA). While it sounds benevolent, there is, of course, a catch. In exchange for housing, food, and the provisioning of nearly every need imaginable, individuals in the DOLA communities would work for Amazon, for free. In Josh’s final presentation, he explained the way in which individuals would be assigned jobs within DOLA communities, the way the provisioning of housing would work, the way the DOLA communities would begin and the order of operations for growing the community and adding more residents and occupations/industries, and the myriad advantages for Amazon, effectively at this stage a logistics company, in having a community of individuals on whom it can test every facet of its business, from shipping to transit to healthcare.

Josh decided on a series of “beta-testing” locations for the project based on an in-depth research process that analyzed land usage and public policies in the various countries in which each DOLA would be located. Josh also analyzed the financial feasibility and potential financial benefits for Amazon and declared that it would be a very successful venture should Amazon pursue it. His final presentation was effectively a pitch for the project, which was both inspiring and deeply disturbing.

Josh decided on a series of “beta-testing” locations for the project based on an in-depth research process that analyzed land usage and public policies in the various countries in which each DOLA would be located. Josh also analyzed the financial feasibility and potential financial benefits for Amazon and declared that it would be a very successful venture should Amazon pursue it. His final presentation was effectively a pitch for the project, which was both inspiring and deeply disturbing.

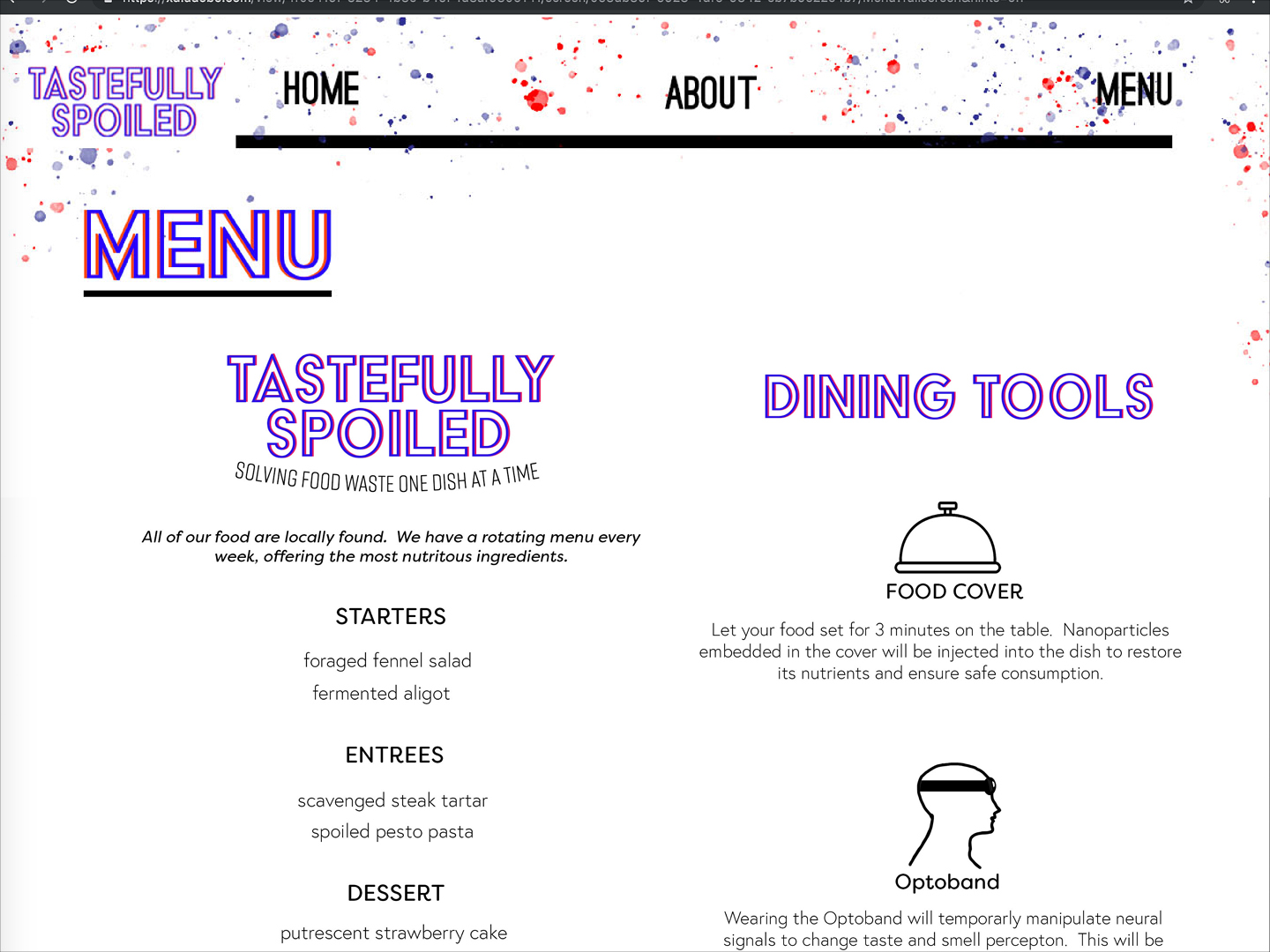

Above: Liz Vangyi produced a fascinating project about the future of food waste. She was interested in what happens as the global population increases and food becomes, relative to population, scarcer. She suggested that one of the root causes of food scarcity was actually food waste. Instead of focusing on futures in which food production would be augmented through technological or other means, Liz chose to focus on recuperating food that had been wasted by turning it into a luxury dining experience with emergent technologies. Her speculative project, called Tastefully Spoiled, proposed a future in which, “by using nanotechnology and optogenetics, we can bring nutritional value to food and make it safe to eat again.” Tastefully Spoiled is thus “a speculative dining experience of eating food waste with special tools.”

/TEACHING

Some Notes on the Interaction Design Course (2017-2019) at Michigan State University

Since arriving at Michigan State University, I have taught various iterations of our Interaction Design course. Beginning in 2017, I experimented with an Interaction Design pedagogy that approach the content with a holistic lens that includes both the fundamentals of doing interaction design while at the same time situating that practice within a historical political-economic context and technoscientific milieu. Without an understanding of the ways our technologies come to be and the ideologies that shape them, these technologies and the forms they take (along with the politics they help enact and the ideologies they prop up) become naturalized in society. This results in students accepting the existence of particular technologies (and by association, therefore, the politics of those technologies) without considering how things might be otherwise. Indeed, one of the core contentions of the course is that the very thing that the students design—the interface—conceals the fact that things could be different. [1]

Weaving together the fundamentals of professional interaction design and the contextual study of computing (drawing on literature and approaches from Science and Technology Studies) was a challenge, and this exposition is not meant to suggest that what I attempted during these years was successful.

In the iterations of the course that began to take shape in the fall of 2017, the course became composed of four separate movements. The first was a short exercise that we do together as a class, and actually isn’t really a project at all. That is, we read a book together. In 2017, that book was Metahaven’s Can Jokes Bring Down Governments? In 2018, we read Nick Srnicek’s Platform Capitalism. These texts introduced students to a broader conception of interaction design, not merely as a benign instrument of capital but rather as a political, economic, and cultural practice that has real consequences. The second project introduced students to some of the basics of programming for the web, while the third project introduced students to the conceptual and technical linkages between database and interface. [2]

In the fall of 2017, and subsequently in 2018 and 2019, I assigned a final project that sought to contextualize the work of interaction designers within a broader technological, sociopolitical, economic, and historical background.

This project asked students to watch The Trap and All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace—two films by the British director Adam Curtis—and to try to triangulate their work as designers with the films’ examinations of relationships between technology and society, and the unintended consequences that precipitate from these relationships. Students viewed the films, select specific historical figures or themes from the films and research those figures or themes in more detail than Curtis presents, and produced a proposal and prototype for an interactive (hybrid physical/digital) project that expresses that research for a particular audience.

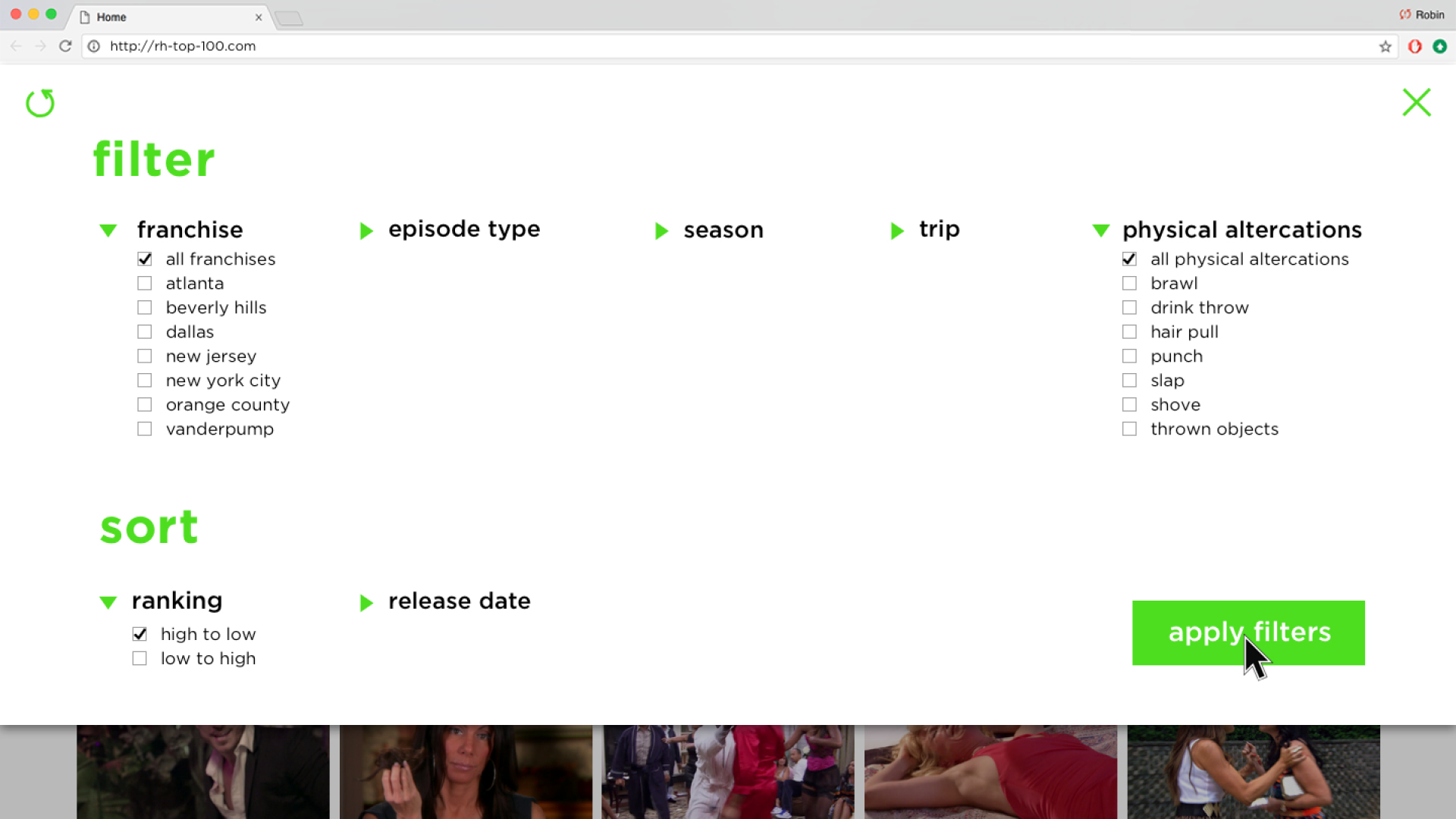

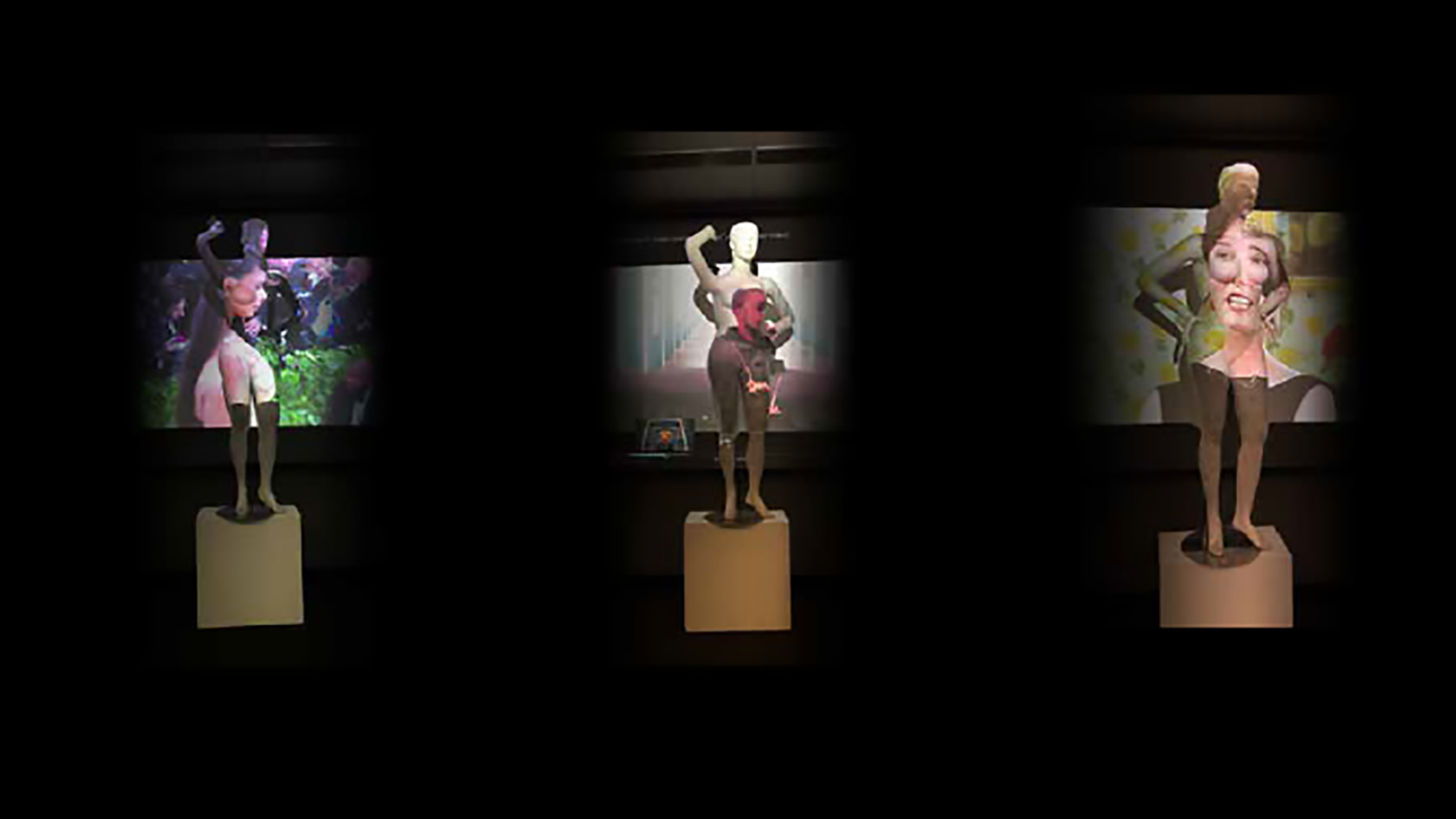

Below: Robin Talbert positioned herself as a “Real Housewives Historian” and developed a database and taxonomic conventions for the second project.

Since arriving at Michigan State University, I have taught various iterations of our Interaction Design course. Beginning in 2017, I experimented with an Interaction Design pedagogy that approach the content with a holistic lens that includes both the fundamentals of doing interaction design while at the same time situating that practice within a historical political-economic context and technoscientific milieu. Without an understanding of the ways our technologies come to be and the ideologies that shape them, these technologies and the forms they take (along with the politics they help enact and the ideologies they prop up) become naturalized in society. This results in students accepting the existence of particular technologies (and by association, therefore, the politics of those technologies) without considering how things might be otherwise. Indeed, one of the core contentions of the course is that the very thing that the students design—the interface—conceals the fact that things could be different. [1]

Weaving together the fundamentals of professional interaction design and the contextual study of computing (drawing on literature and approaches from Science and Technology Studies) was a challenge, and this exposition is not meant to suggest that what I attempted during these years was successful.

In the iterations of the course that began to take shape in the fall of 2017, the course became composed of four separate movements. The first was a short exercise that we do together as a class, and actually isn’t really a project at all. That is, we read a book together. In 2017, that book was Metahaven’s Can Jokes Bring Down Governments? In 2018, we read Nick Srnicek’s Platform Capitalism. These texts introduced students to a broader conception of interaction design, not merely as a benign instrument of capital but rather as a political, economic, and cultural practice that has real consequences. The second project introduced students to some of the basics of programming for the web, while the third project introduced students to the conceptual and technical linkages between database and interface. [2]

In the fall of 2017, and subsequently in 2018 and 2019, I assigned a final project that sought to contextualize the work of interaction designers within a broader technological, sociopolitical, economic, and historical background.

This project asked students to watch The Trap and All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace—two films by the British director Adam Curtis—and to try to triangulate their work as designers with the films’ examinations of relationships between technology and society, and the unintended consequences that precipitate from these relationships. Students viewed the films, select specific historical figures or themes from the films and research those figures or themes in more detail than Curtis presents, and produced a proposal and prototype for an interactive (hybrid physical/digital) project that expresses that research for a particular audience.

Below: Robin Talbert positioned herself as a “Real Housewives Historian” and developed a database and taxonomic conventions for the second project.

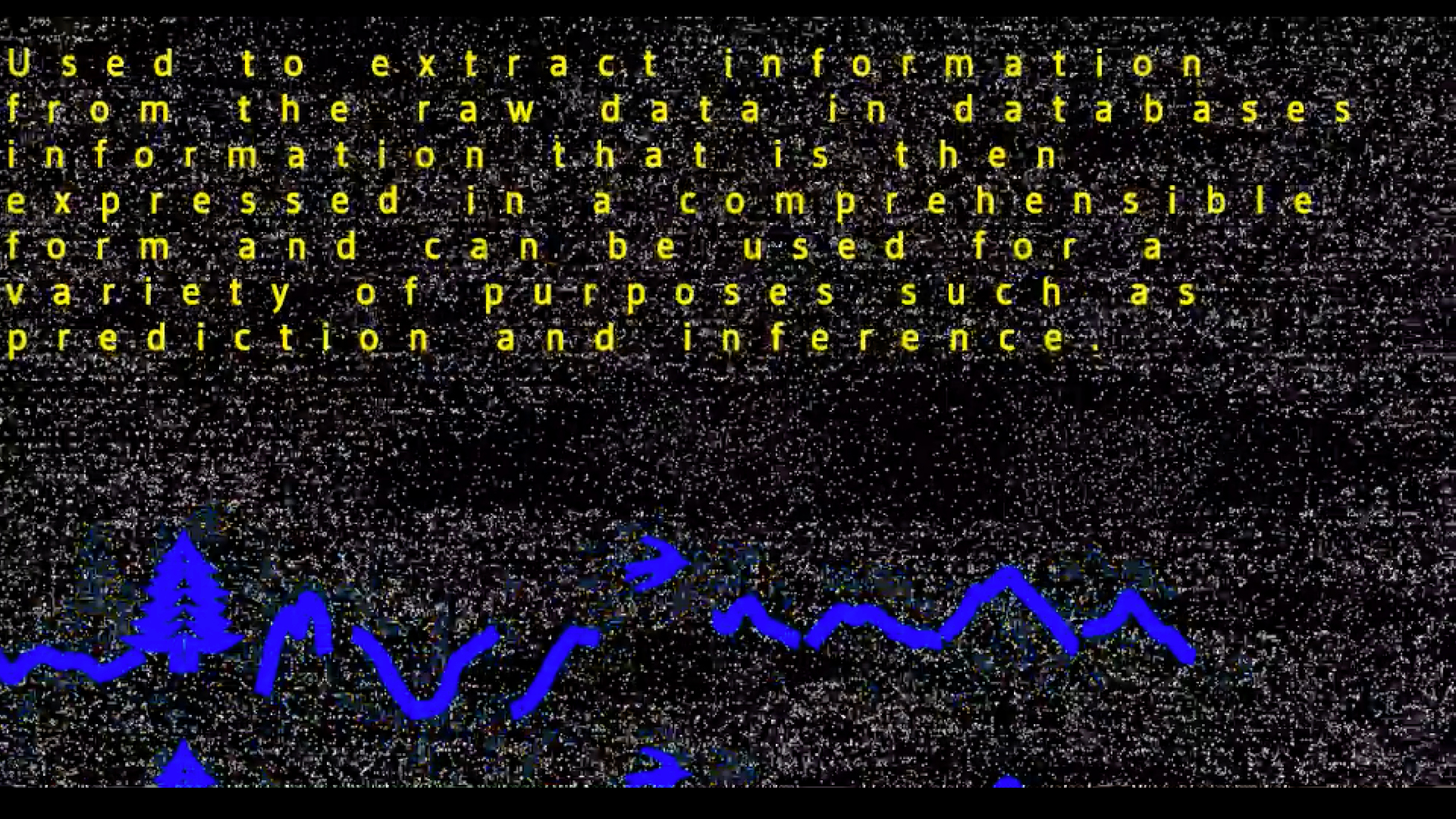

Below: Nikki Dallich (BFA '19) proposed a project to bring the impacts of algorithmic inference and recommendation, and its incisive shaping of the contours of everyday life, to her classmates in the Art Department, specifically those who shop at the little Art Supply Store (which also sells snacks, coffee, and other beverages). She therefore produced a prototypical application that would sit on a device alongside the credit card machine and make recommendations to users based on their purchase history at the store. Her intervention, however, was interestingly performative, in that she controlled the prototype from her computer, and, even for users paying cash, would recommend things to them, supposedly based on what they had purchased. In this sense, her project also suggests a future in which we are all algorithmically anticipated, and makes this future apparent to her classmates.

Above: Christina Dennis (BFA '19) researched the past, present, and future of social credit scoring. She wrote a short essay arguing that Ayn Rand’s objectivism and the individualist “Californian Ideology” associated with 1990s Silicon Valley entrepreneurialism that Rand inspired were, paradoxically, similar to both the Chinese Social Credit Scoring system and to the underlying thrust of two episodes of Black Mirror (“ten million merits” and “nosedive”). This similarity, she suggested, positioned the ideal participant in society as an individual living out selfish desires. In the case of the social credit scoring system, this selfish desire is the desire for a higher score; meanwhile, a Randian approach would suggest that to behave in one’s own self-interest would inherently make one a better member of society. In neither case, however, is the individual motivated by altruism.

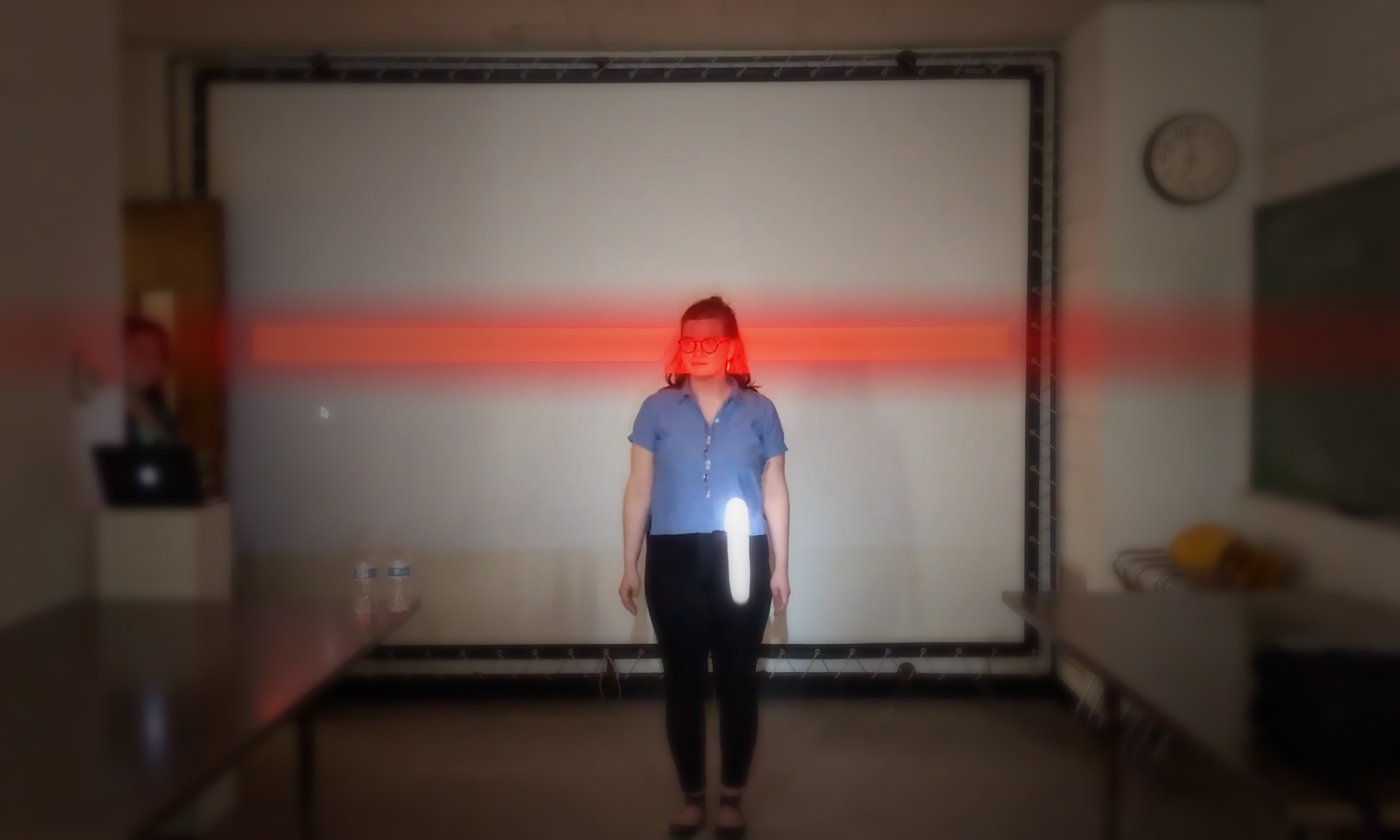

Part of Christina's piece was a performative intervention in which she pretended she was from a company that was beta-testing a social credit scoring system for the US, and that our institution had been chosen as a prototypical “community” for testing. She built a system that allowed users to ostensibly sign in to their social media accounts (the system did not actually capture any of the users’ data), designed a fake “body scan” in which a red line was projected across the entire space where users were standing, and then showed the users what their social credit score would be according to this company’s proprietary algorithms.

Part of Christina's piece was a performative intervention in which she pretended she was from a company that was beta-testing a social credit scoring system for the US, and that our institution had been chosen as a prototypical “community” for testing. She built a system that allowed users to ostensibly sign in to their social media accounts (the system did not actually capture any of the users’ data), designed a fake “body scan” in which a red line was projected across the entire space where users were standing, and then showed the users what their social credit score would be according to this company’s proprietary algorithms.

Above: In fall 2018, students were asked to produce a proposal for a small museum exhibition. One group of students chose to examine the relationship between social media and mental illness, reflecting the role of computing in the history of diagnoses of mental illness (e.g., the history of the DSM).

/TEACHING

Some notes on my 2017 Selected Topics in Graphic Design

(offered spring semester 2017 for Graphic Design BFA students)

In spring 2017, I had the opportunity to teach my first selected topics course. In this class, we addressed the relationship between design and emerging technologies. We talked about the dynamic forces at play when a new technology is developed, and how social and material relations (vis-a-vis political economy) are embedded within or reified by our technologies. Students engaged in three projects: in the first, students unpacked the relations within a given technology; in the second, students sought to identify certain tendencies within a particular technology and design consumer products that would subvert those tendencies; and in the third, students engaged in a short exploration of machine vision technologies.

The first project took its cues from the Implosion Project given by Donna Haraway to one of her writing classes. This project asked students to trace the nature of a technological object, looking at the object as a networked assemblage of materials, patents, corporations, individuals, ideologies, etc. The students were then asked to, given what they learned about the technological artifact they had chosen, express their new knowledge about it as an assemblage through a website/web-based interactive work.

(offered spring semester 2017 for Graphic Design BFA students)

In spring 2017, I had the opportunity to teach my first selected topics course. In this class, we addressed the relationship between design and emerging technologies. We talked about the dynamic forces at play when a new technology is developed, and how social and material relations (vis-a-vis political economy) are embedded within or reified by our technologies. Students engaged in three projects: in the first, students unpacked the relations within a given technology; in the second, students sought to identify certain tendencies within a particular technology and design consumer products that would subvert those tendencies; and in the third, students engaged in a short exploration of machine vision technologies.

The first project took its cues from the Implosion Project given by Donna Haraway to one of her writing classes. This project asked students to trace the nature of a technological object, looking at the object as a networked assemblage of materials, patents, corporations, individuals, ideologies, etc. The students were then asked to, given what they learned about the technological artifact they had chosen, express their new knowledge about it as an assemblage through a website/web-based interactive work.

Above: screenshots of Jenna Culliton’s “implosion” project.

The second project asked students to produce consumer products from the near future that, in some way, subverted a particular sociotechnical tendency (and the way that this tendency might be exacerbated in the future).

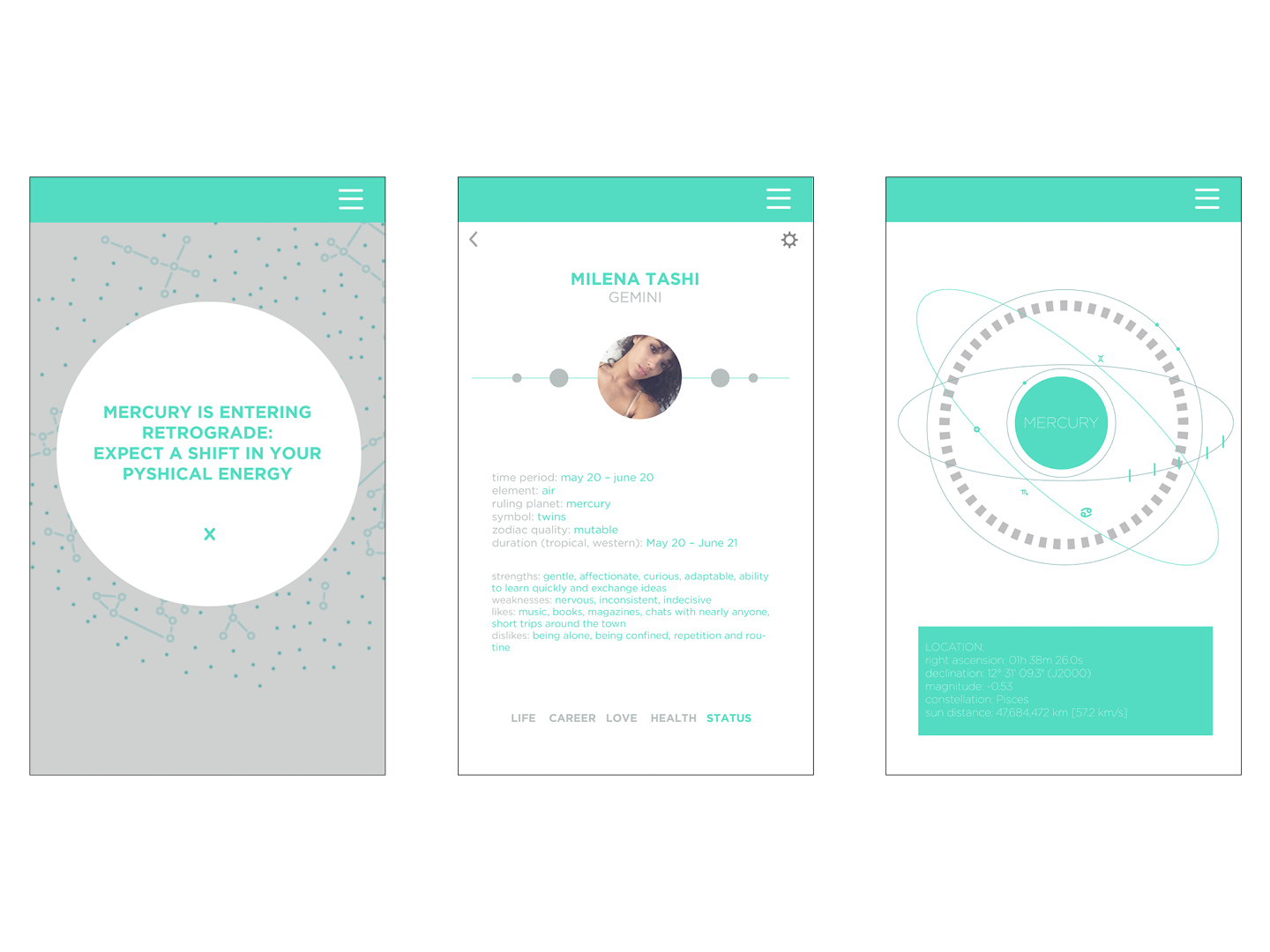

Lorenza Centi’s project, Elixir, proposed the existence of an internet-connected mood-ring and corresponding app that gave users access to the most sophisticated “data-driven astrology.”

From her site:

Elixir, as a fiction, is a whimsical yet biting critique on our obsession with “data-driven” anything, and purports to be more “accurate” than other astrological charts because of its

reliance on big data.

The second project asked students to produce consumer products from the near future that, in some way, subverted a particular sociotechnical tendency (and the way that this tendency might be exacerbated in the future).

Lorenza Centi’s project, Elixir, proposed the existence of an internet-connected mood-ring and corresponding app that gave users access to the most sophisticated “data-driven astrology.”

From her site:

Elixir is a precision tracking system that allows you to follow your astrological chart in real time and space for a more accurate reading. With updates on positions of the sun, moon and planets astrological aspects, and consideration of sensitive angles to allow for more accurate representation of events within your life. Using smart fiber woven textile color changing technology, the elixir ring subtly alerts you or a change in astrological location affecting your sign. Paired with app integration, a custom profile is built on your natal chart and personality traits. Changes in lifestyle categories, including career, life, love and health are then indicated by change in color.

Elixir, as a fiction, is a whimsical yet biting critique on our obsession with “data-driven” anything, and purports to be more “accurate” than other astrological charts because of its

reliance on big data.

Above: images from Lorenza’s Elixir project.

Finally, during the last week of the course, we experimented with the face- and object-tracking features of Google’s Cloud Vision platform. We learned some things about the inherent biases in this platform and the way the data on which it was trained influences how it “sees.”

Finally, during the last week of the course, we experimented with the face- and object-tracking features of Google’s Cloud Vision platform. We learned some things about the inherent biases in this platform and the way the data on which it was trained influences how it “sees.”

Above: A page from Rachel Davis’ 68-page book of Google Cloud Vision JSON output.

/TEACHING

Some Notes on Teaching “Design Thinking” (2015-2016) (yes... I know... the title, ugh).

Michigan State University

I spent the summer of 2015 redesigning the curriculum for our “Design Thinking” course, which, thankfully, we eliminated the following year. Nonetheless, below is some information about the curriculum redesign which I think is worth having some archive of:

There are two important assumptions that structure the curriculum for this class: 1) Design has to be “about” something; and, 2) “Design” is not form-determining, meaning that it does not matter what exactly students make — it could be a proposal or prototype for an app, or it could be a proposal for a speculative design project that provokes discourse about the future; it could be an event or it could be a service. It really doesn’t matter as long as they traverse through the process.

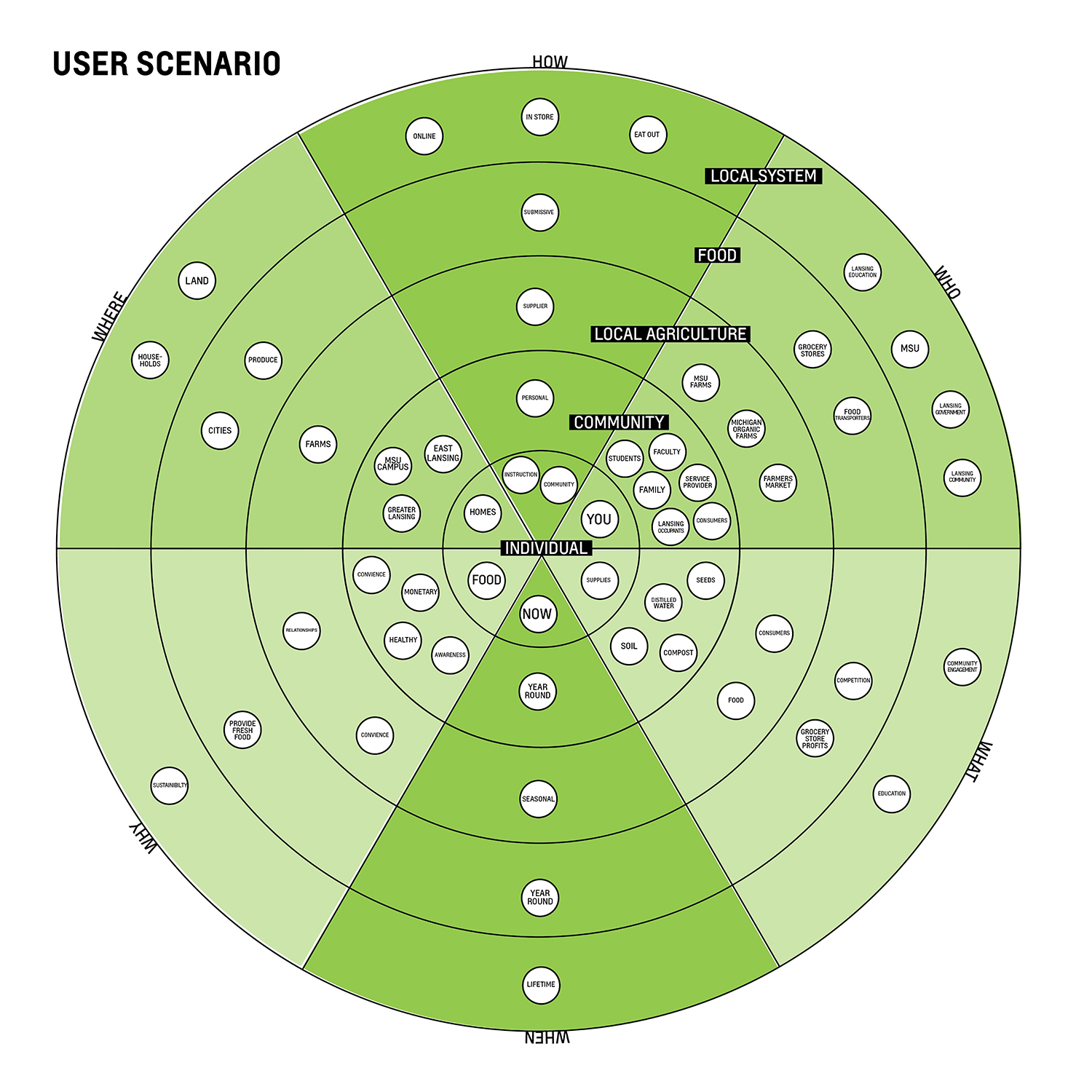

Because design must be about something, I have chose to make the Design Thinking class operate kind-of like a special topics class. The theme the course became, very broadly, "food," and the research question that students were asked to address was: “How can design interventions change or shape someone’s relationship to the food system?” I spent the spring and summer researching food systems. During the spring semester, I joined MSU’s Food Justice and Food Sovereignty research group, which is part of the Center for Regional Food Systems at MSU.

At the outset of the semester, I framed the design process for students by introducing, and subsequently subverting, Herbert Simon’s famous dictum: “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” I suggest to the students that we understand Simon’s dictum in a way he probably wouldn’t approve of: that there are an infinite number of existing conditions and an infinite number of preferred conditions, and those existing and preferred situations depend, to a great degree, on who (or what) we are privileging. Who really is the user of an iPhone? Is it the person in whose hands the iPhone ends up? Or is it the person on the assembly line whose hands it passes through? This is important because ideas like “usability” are subjective and can be used by certain individuals and corporations in order to perpetuate the hegemony of certain ideologies. Just because Apple’s Health app or the fitbit is “usable” doesn’t mean it’s a good idea for me to track and give over my health data to a corporation in the first place. As a scholar who is also a designer and an artist, I believe it is an ethical imperative for design education to open students eyes to the rhetoric that infuses their interactions with designed objects and experiences and to be able to interrogate the ideologies driving such rhetoric.

The first two weeks of the semester were filled with readings about different kinds of design, ranging from product design to graphic design to interaction and experience design, but also including readings on speculative design, adversarial design, and transition design. I emphasize the importance of being forward-thinking and futures-oriented. I gave a series of lectures on a variety of projects that I saw as the direct result of the design process—these projects were not necessarily “design projects” in the sense that one might think of design projects. The works I showed ranged from Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Gramsci monument” to a food truck in the Bronx to an app about tracking produce to an art installation about Wonderbread that I worked on with several other designers.

The week following this introduction to “design in the expanded field,” I introduced students to the variety of scholarship that deals with food and food systems. Readings ranged from anthropological studies of cultural foodways to research on GMOs to government reports on food hubs.

After these three weeks of introduction to design and the topic of food/food systems, students were given the freedom to do three weeks of research on a topic of their choosing within the food/food systems framework.

After doing an extensive amount of research on their chosen topics, the students created concept maps of their research and developed detailed annotated bibliographies of their research (which could include a variety of methods of gathering research, ranging from scholarly research to in-person interviews and observational research).

Students then transitioned from the research phase of the semester into the “Synthesis and Ideation” phase of the semester. During this phase they synthesized their research in order to articulate several “existing” situations within their topic space. Then, for each existing situation, they identified several “preferred” situations, and for each “preferred” situation, several different ideas for design interventions.

They then narrowed their ideas, explored three of them more deeply, and selected one with which to move forward into the final phase of the semester, in which they are asked to communicate their idea for their design intervention. I ask them to consider what combination of deliverables will best get the idea across. Is it an actual prototype? Is it a video that makes the use of the object/service believable without designing or prototyping it? Is it a combination of digital and physical objects that appear to be from some dystopian future? How will the audience best understand what the experience of this design intervention would be like?

The following are some examples of the results of their research inquiries.

Michigan State University

I spent the summer of 2015 redesigning the curriculum for our “Design Thinking” course, which, thankfully, we eliminated the following year. Nonetheless, below is some information about the curriculum redesign which I think is worth having some archive of:

There are two important assumptions that structure the curriculum for this class: 1) Design has to be “about” something; and, 2) “Design” is not form-determining, meaning that it does not matter what exactly students make — it could be a proposal or prototype for an app, or it could be a proposal for a speculative design project that provokes discourse about the future; it could be an event or it could be a service. It really doesn’t matter as long as they traverse through the process.

Because design must be about something, I have chose to make the Design Thinking class operate kind-of like a special topics class. The theme the course became, very broadly, "food," and the research question that students were asked to address was: “How can design interventions change or shape someone’s relationship to the food system?” I spent the spring and summer researching food systems. During the spring semester, I joined MSU’s Food Justice and Food Sovereignty research group, which is part of the Center for Regional Food Systems at MSU.

At the outset of the semester, I framed the design process for students by introducing, and subsequently subverting, Herbert Simon’s famous dictum: “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” I suggest to the students that we understand Simon’s dictum in a way he probably wouldn’t approve of: that there are an infinite number of existing conditions and an infinite number of preferred conditions, and those existing and preferred situations depend, to a great degree, on who (or what) we are privileging. Who really is the user of an iPhone? Is it the person in whose hands the iPhone ends up? Or is it the person on the assembly line whose hands it passes through? This is important because ideas like “usability” are subjective and can be used by certain individuals and corporations in order to perpetuate the hegemony of certain ideologies. Just because Apple’s Health app or the fitbit is “usable” doesn’t mean it’s a good idea for me to track and give over my health data to a corporation in the first place. As a scholar who is also a designer and an artist, I believe it is an ethical imperative for design education to open students eyes to the rhetoric that infuses their interactions with designed objects and experiences and to be able to interrogate the ideologies driving such rhetoric.

The first two weeks of the semester were filled with readings about different kinds of design, ranging from product design to graphic design to interaction and experience design, but also including readings on speculative design, adversarial design, and transition design. I emphasize the importance of being forward-thinking and futures-oriented. I gave a series of lectures on a variety of projects that I saw as the direct result of the design process—these projects were not necessarily “design projects” in the sense that one might think of design projects. The works I showed ranged from Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Gramsci monument” to a food truck in the Bronx to an app about tracking produce to an art installation about Wonderbread that I worked on with several other designers.

The week following this introduction to “design in the expanded field,” I introduced students to the variety of scholarship that deals with food and food systems. Readings ranged from anthropological studies of cultural foodways to research on GMOs to government reports on food hubs.

After these three weeks of introduction to design and the topic of food/food systems, students were given the freedom to do three weeks of research on a topic of their choosing within the food/food systems framework.

After doing an extensive amount of research on their chosen topics, the students created concept maps of their research and developed detailed annotated bibliographies of their research (which could include a variety of methods of gathering research, ranging from scholarly research to in-person interviews and observational research).

Students then transitioned from the research phase of the semester into the “Synthesis and Ideation” phase of the semester. During this phase they synthesized their research in order to articulate several “existing” situations within their topic space. Then, for each existing situation, they identified several “preferred” situations, and for each “preferred” situation, several different ideas for design interventions.

They then narrowed their ideas, explored three of them more deeply, and selected one with which to move forward into the final phase of the semester, in which they are asked to communicate their idea for their design intervention. I ask them to consider what combination of deliverables will best get the idea across. Is it an actual prototype? Is it a video that makes the use of the object/service believable without designing or prototyping it? Is it a combination of digital and physical objects that appear to be from some dystopian future? How will the audience best understand what the experience of this design intervention would be like?

The following are some examples of the results of their research inquiries.

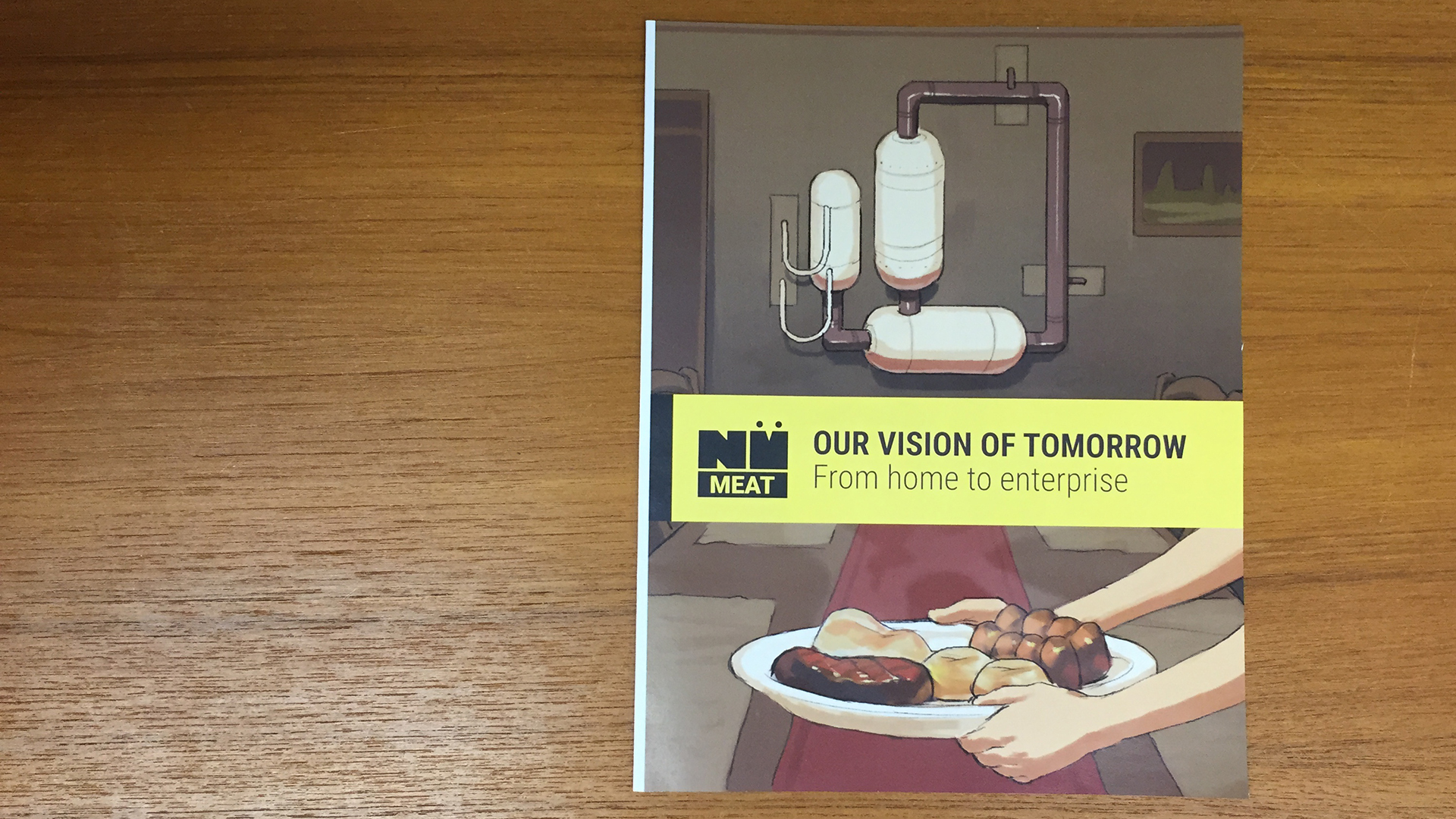

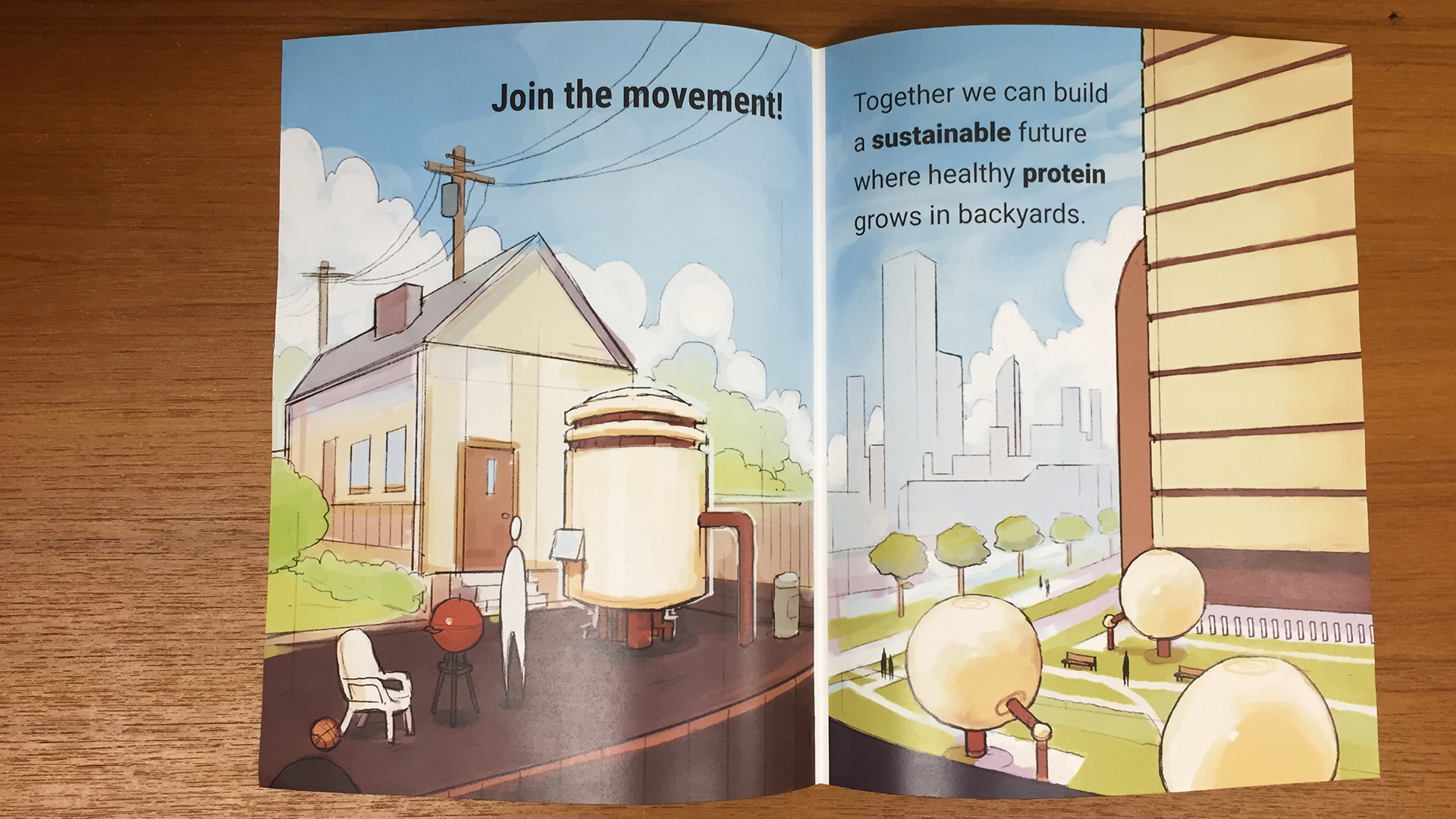

This student researched the future of protein production and consumption. His research ended up centering around mycoprotein (a fungus-based protein). The research ranged from the values and cultural implications of consuming various meat-replacement proteins to the science of producing mycoprotein itself. He produced a futures-oriented design intervention. His work proposes that we entertain the possibility of a world where mycoprotein producing vessels can dot the landscape and become part of the decor of our homes. The work does not suggest that this future is either utopian or dystopian, but rather presents it as one possibility, and asks us to consider whether or not such a future is desirable.

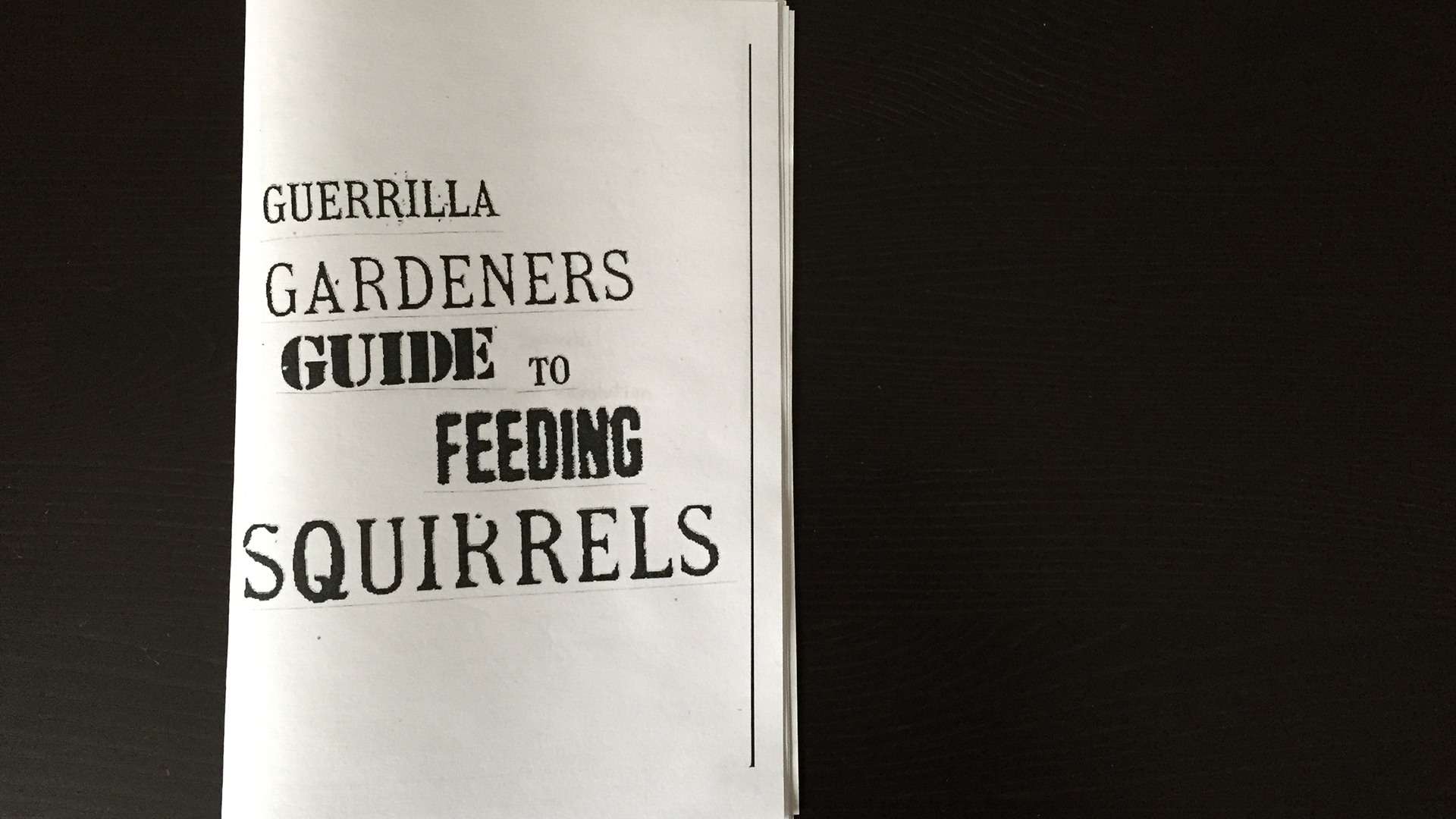

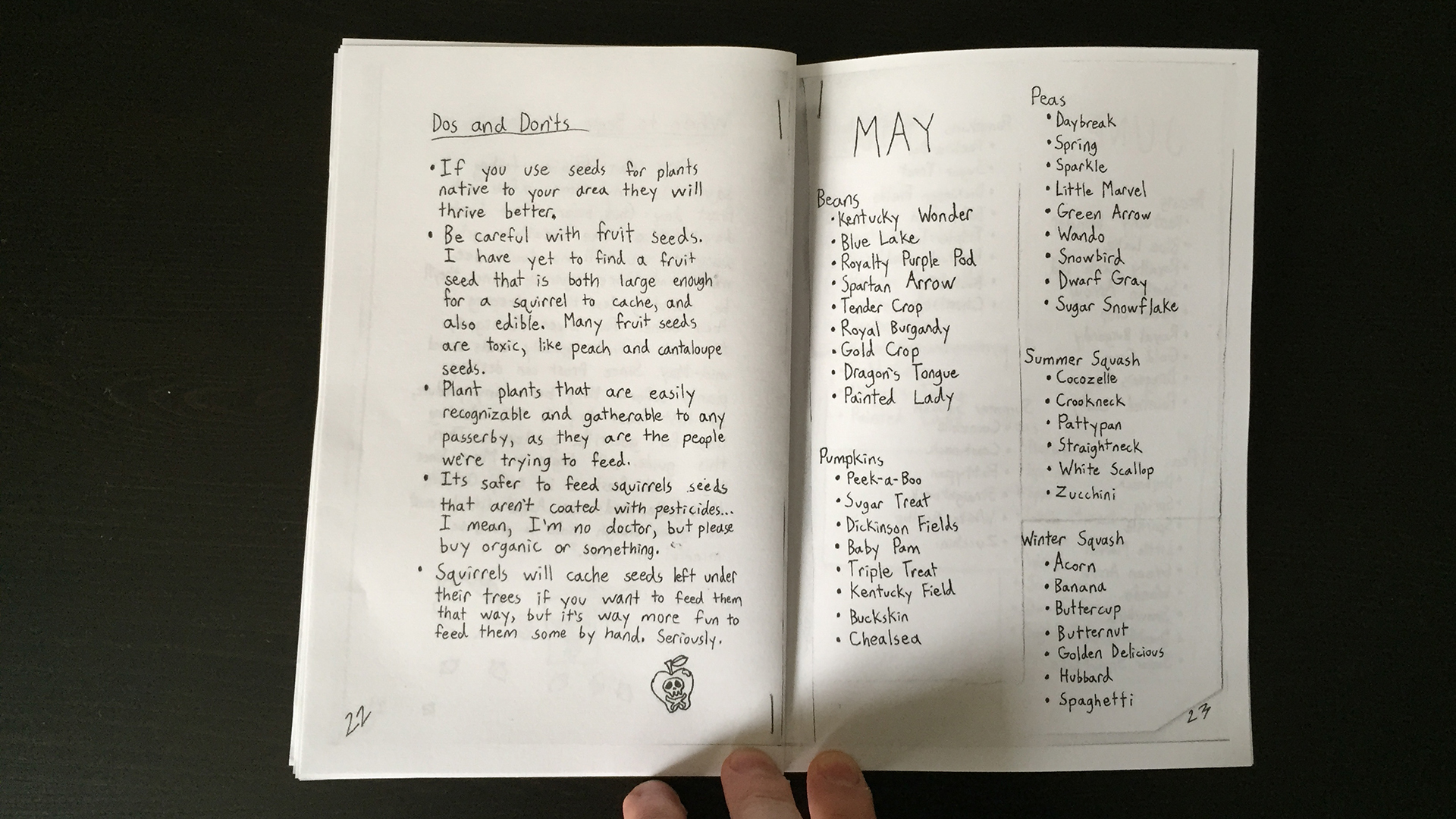

This student began the semester researching ways in which communities could become more resilient and food secure. A burgeoning interest in guerrilla gardening led him to learning more about the ways in which current legal systems and structures often prevent communities from engaging in agricultural projects that would help develop food resilience and security. He identified a potential conspirator — the gray squirrel. After learning about the way squirrels eat and cache seeds, he realized squirrels could operate almost as proxy guerrilla gardeners. The student developed a ‘zine and a toolkit entitled “The Guerrilla Gardener’s Guide to Feeding Squirrels.”

Design Thinking (Spring 2016)

After a semester from which I learned a great deal about teaching “design” — in the broadest sense — to students who do not come from an art and design background, I decided to retain the majority of my STA 303 (Design Thinking) curriculum from the fall semester of 2015, and make minor revisions in order to better understand which aspects of the structure I had developed needed more work.

The primary revision I made was that, instead of working individually, students worked in groups. I designed these groups such that no group had more than two students from the same major, and, in most cases, the groups did not have any students who shared a major. These groups remained the same throughout the duration of the semester. I anticipated that students would feel more comfortable engaging in more ambitious projects and would arrive more quickly at prototypes when working in groups. This assumption was not necessarily accurate. Students had a much more difficult time identifying a specific research area, and they tended to struggle in their attempt to identify particular problems that their intervention might address. At the same time, the work the students produced often reflected the different disciplines from which those students came.

The theme of the course remained the exploration of the design of food systems, and the thorough investigation of one aspect of the food system as a starting point for the development of an intervention that transforms our relationship to it. The course retained its openness to experimental design projects, and I worked to further develop students’ understanding of the variety of design practice in the world. I even managed to get Zack Denfeld, founder of the Center for Genomic Gastronomy — an experimental art and research group whose work has been internationally recognized and exhibited — to Skype into our class from his studio in Ireland.

The Design Thinking class transcends the canonical business school definition of “design thinking” by introducing students (who are not design students) to the plurality of design disciplines, ranging from traditional kinds of design, like graphic design and industrial design, to more experimental forms being practiced along the margins today, such as speculative design and adversarial design.

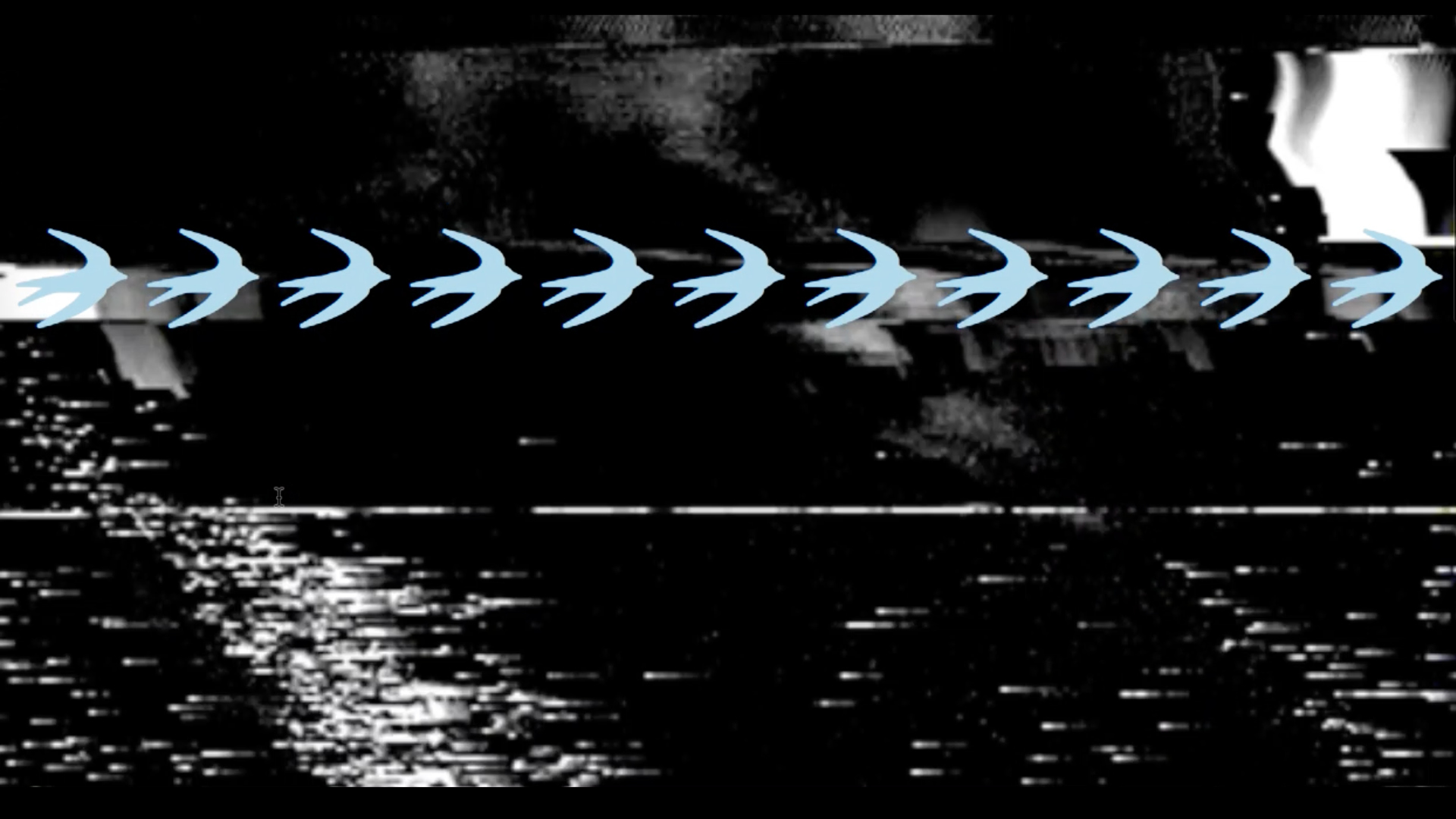

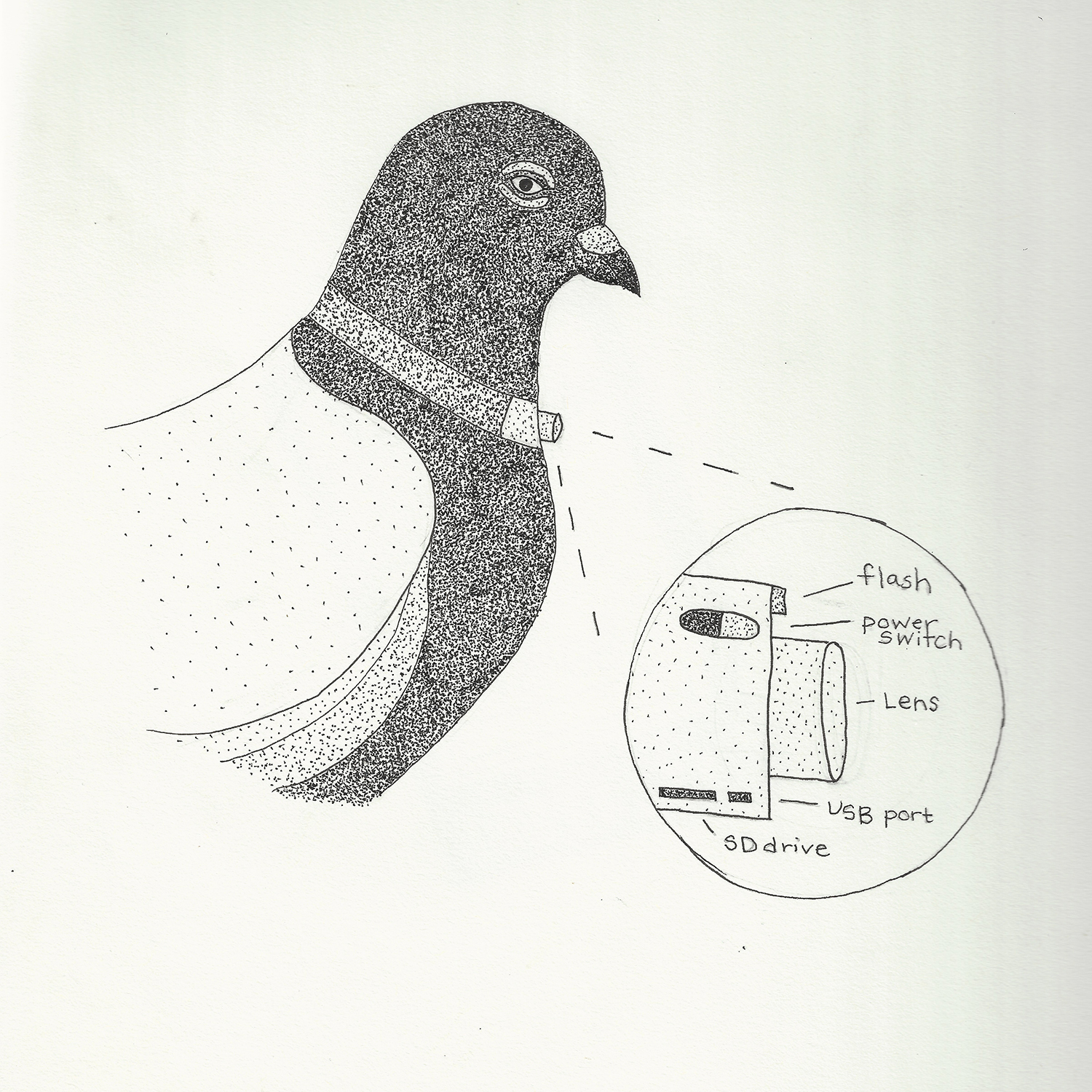

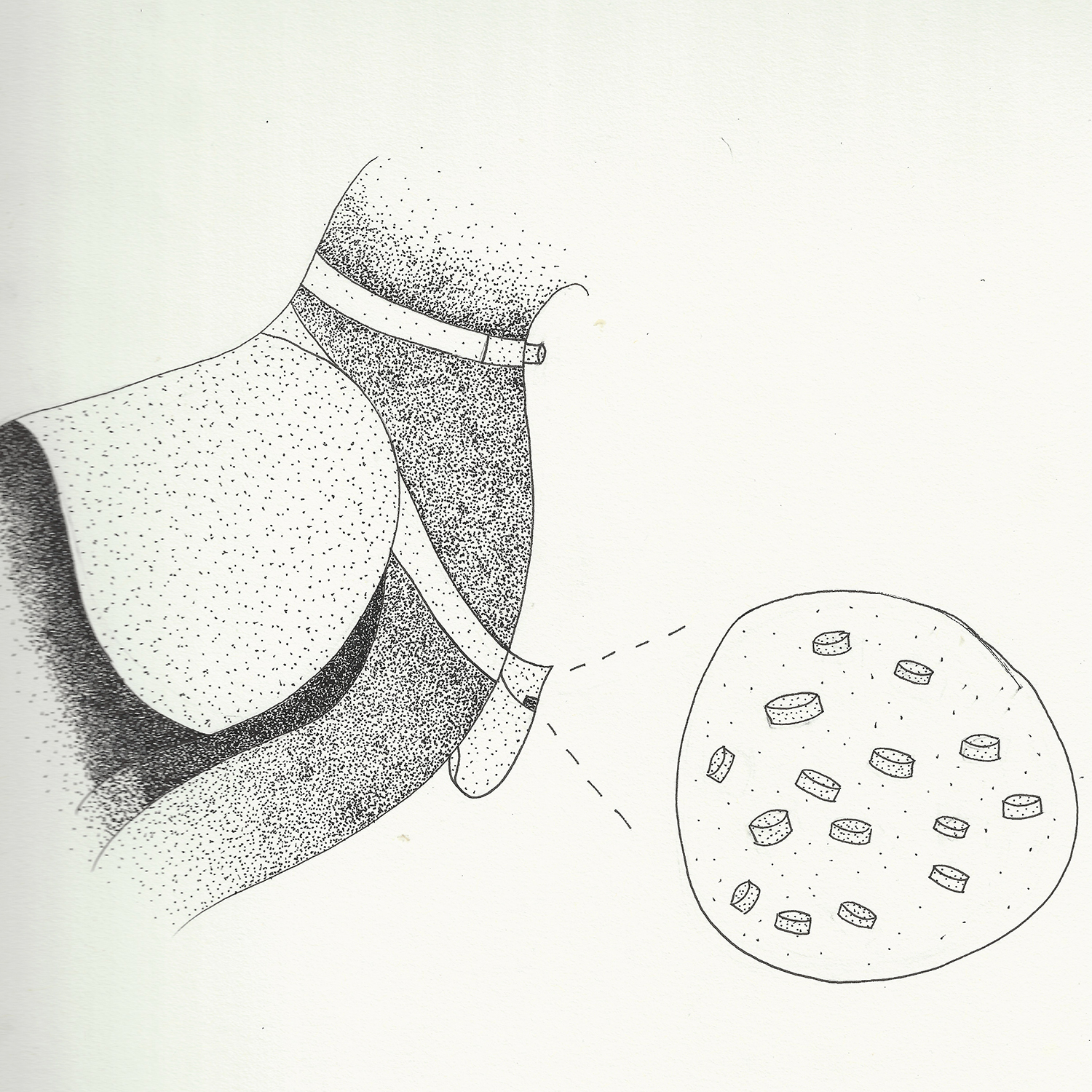

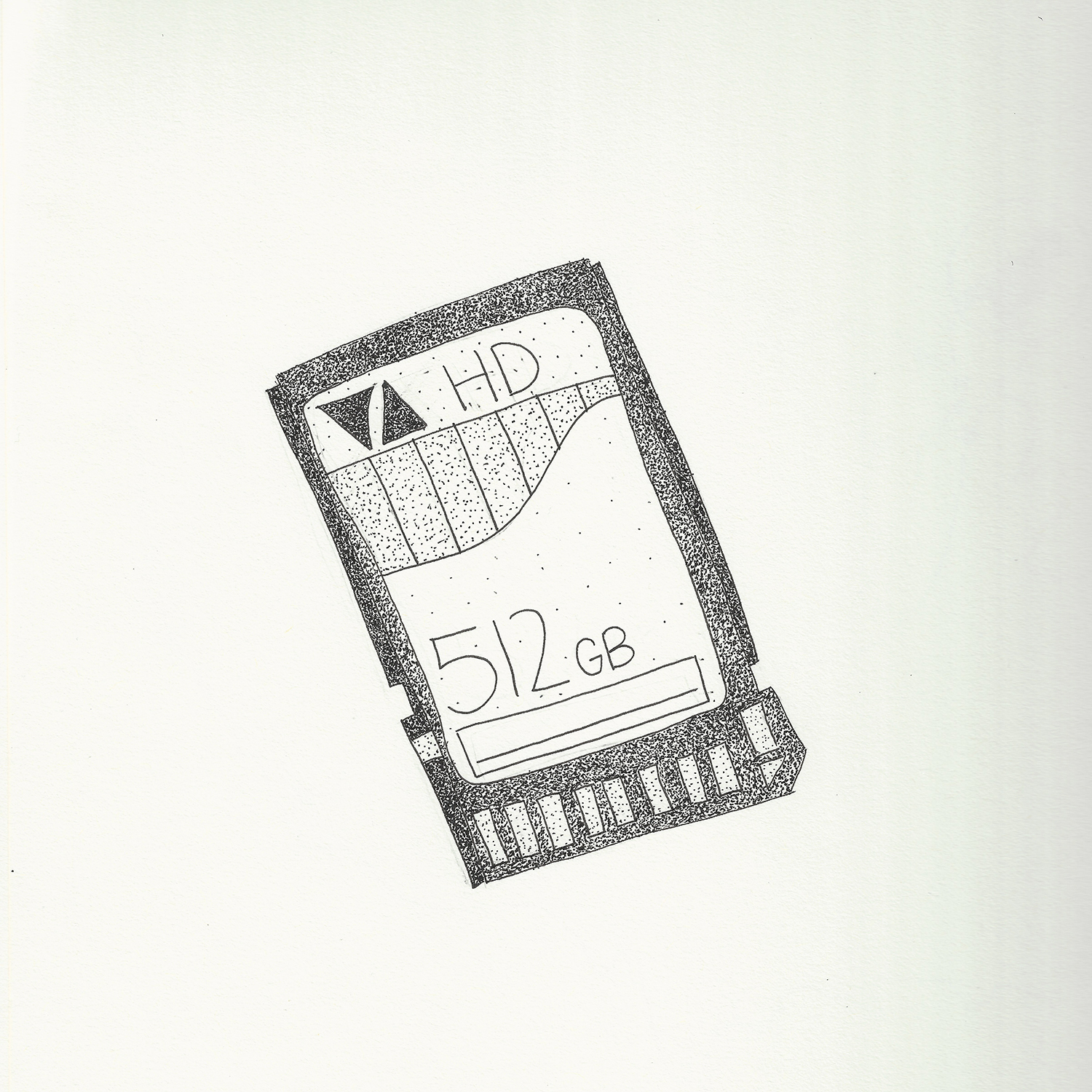

While researching the obfuscation of food supply chains (and the surprising legality of such obfuscation), this project team also became interested in design fiction, speculative design, and critical design. They decided to create a system of artifacts that demonstrate the existence and operations of a fictional subversive group, members of which combine emerging technologies with the training of pigeons in order to document the undisclosed supply chains of different food products as they are shipped around the globe. By presenting their classmates and others who viewed their work with a world in which such a group would reasonably exist, the project team sough to interrogate the ability of food companies to keep their supply chains secret, eliciting questions about the mysterious sources of many of the food products we eat every day.

While researching the obfuscation of food supply chains (and the surprising legality of such obfuscation), this project team also became interested in design fiction, speculative design, and critical design. They decided to create a system of artifacts that demonstrate the existence and operations of a fictional subversive group, members of which combine emerging technologies with the training of pigeons in order to document the undisclosed supply chains of different food products as they are shipped around the globe. By presenting their classmates and others who viewed their work with a world in which such a group would reasonably exist, the project team sough to interrogate the ability of food companies to keep their supply chains secret, eliciting questions about the mysterious sources of many of the food products we eat every day.

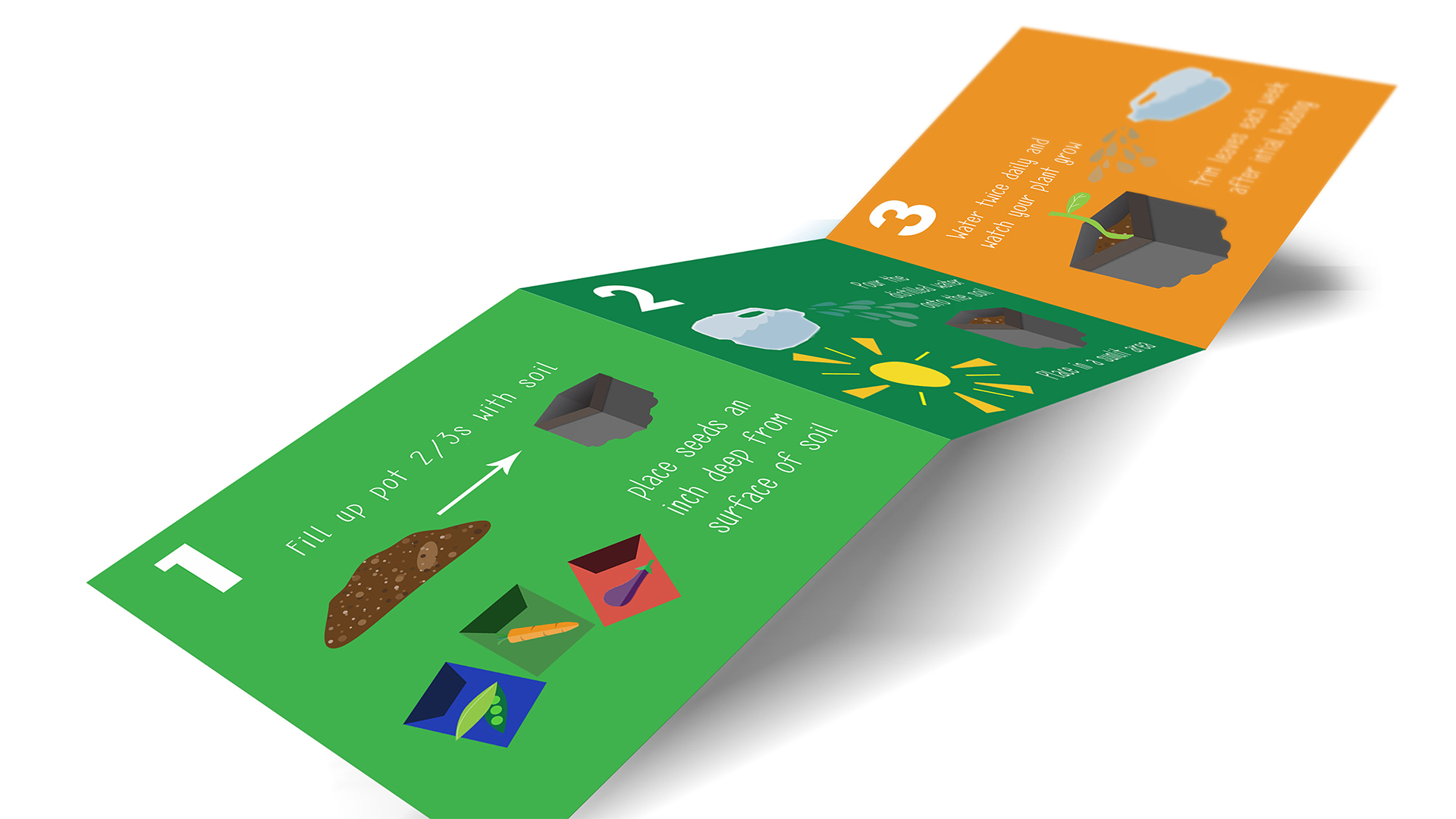

Grow Yourself is a service system that empowers people to grow their own healthy produce, while involving traditional produce retailers (both grocery stores and farmers markets) in a new relationship with consumers wherein both parties take on new roles and benefit from them. The service makes basic gardening kits readily available for students at Michigan State University and within the Lansing community. The team members were not graphic design students, though some were more familiar with the design process than others.